Irish Australian Legal Links

The life, the times, the legend of Ned Kelly — bushranger, outlaw, to some folk hero — is perhaps demonstrative of the conundrum presented when one comes to examine the Irish influence in Australian legal history.

Speech by John (Jack) Rush QC, Chairman of the Victorian Bar, to the Irish Bar Conference, Sydney, 28 August 2003.

Ned Kelly, of humble Irish parentage, sought to revenge wrongs committed on his mother, sisters and brothers by a corrupt constabulary of Irish origins. Kelly, in the company of his outlaw gang all of Irish extraction, shot Police Constables Lonigan, Scanlon and Kennedy, all of Irish extraction. When eventually caught, he was tried before and when found guilty sentenced to be hanged by Sir Redmond Barry, Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria. Barry was a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, formerly of the Irish Bar. Offender, victim, judge and no doubt more than half the jury were all of Irish background.

Let me set the 1870s social scene with a quote from Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie letter. This is a rambling letter Ned Kelly wrote in an attempt to explain his actions. After robbing the bank at Jerilderie and before taking off with the booty Ned left the letter with a Bank clerk for the purpose of publication. It was published widely and added to his contemporary legendary status. It was also used against him in his murder trial (actually it was never presented in court .ed):

I am reconed a horrid brute because I had not been cowardly enough to lie down for them under such trying circumstances and insults to my people … I have been wronged and my mother and four or five men lagged innocent and is my brothers and sisters and my mother not to be pitied also who has no alternative only to put up with the brutal and cowardly conduct of a parcel of big, ugly, fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splay-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords which is better known as officers of justice or Victorian Police … a policeman is a dis- grace to his country … next he is a traitor to his country and ancestors and religion as they were all Catholics before Saxons and Cranmore yoke held sway … what would people say if they saw a strapping big lump of an Irishman shepherding sheep for 15 bob a week or tailing turkeys in Tallarook ranges for a smile from Julia … they would say he ought to be ashamed of himself and tar-and-feather him. But he would be a king to a policeman who for a lazing loafing cowardly bait left the ash corner deserted the shamrock – the emblem of true wit and beauty to serve under a flag and a nation that has destroyed massacred and murdered their fore-fathers …

At the time of writing the letter Kelly was approximately 23 years of age. It can be seen that in the Irish tradition, with little or no education, Ned Kelly was an advocate and his speech from the dock in his murder trial bears testament to this.

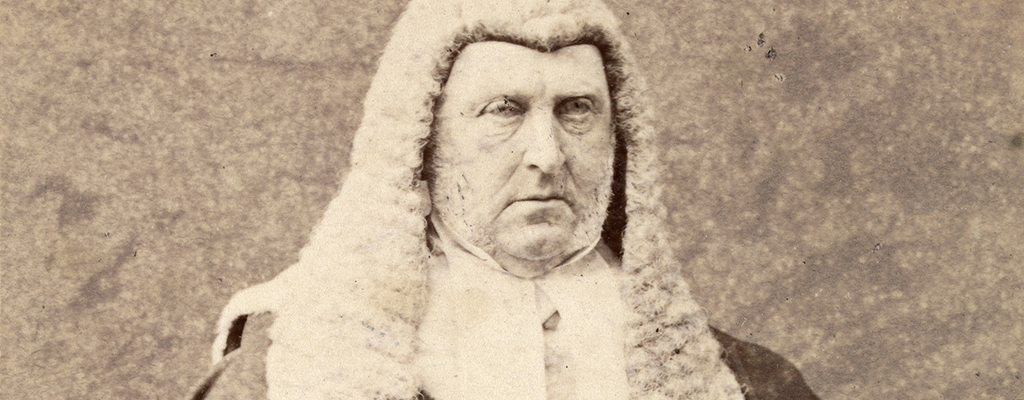

Kelly’s trial judge represented a different Irish contribution to Australian law. Redmond Barry came to Australia from the Four Courts, Dublin, in 1839.

A recent biography of his life records that even on his sea journey to Australia he was controversial. He commenced a liaison with the wife of a senior government official of the then colony of New South Wales. The biographer noted that in his diary of the sea journey Barry placed an asterisk at each date he managed intercourse on the voyage. There was an impressive tally. As the voyage wore on he entered the details like a cricket score. 31/7 Mrs S twice — 6/8 Mrs S four times. The affair raged on despite the passengers being scandalised by the behaviour. The scandal meant he was packed off to the then separate colony of Victoria.

Sir Redmond Barry was part of the class referred to as the Anglo-Irish. They were the establishment Irish, integral to the colonial process. In pre gold rush Australia:

… the Irish were local representatives of the Anglo-Irish ascendency, an Irish cousinage of gentlemen whose lineage, connections, wealth and social position … were granted superiority in “colonial society”. They were, the best of them, in the words of Mahaffy, the provost of Trinity College in which so many of them were educated, heroic, splendid mongrels, a mixed breed in decline and increasingly alien in their own Ireland … yet feeling themselves Irish and indeed formed by distinctive and unique Irish attitudes and experience … Australia was their chance to realise frustrated Irish ambitions. The Anglo-Irish were central to every proposal of liberal reform during this era.

At his trial Kelly was represented by an inexperienced barrister, less than a year’s call at the Bar. Bindon had never appeared in the Supreme Court. He failed to adequately to put a case of self-defence or manslaughter. Kelly according to the laws of the time was unable to give evidence. After the verdict was announced the Judge’s Associate asked Kelly if he had anything to say as to why sentence should not be passed. A remarkable exchange between Bench and dock then ensued.

Kelly, long silent, commented on the proceedings “… Bindon knew nothing about my case” — that on the evidence presented “… no juryman could have given any other verdict”. Kelly stated that if he had examined the witnesses “… I am confident, I would have thrown a different light on the case”. Kelly said he did not cross examine because he did not want to appear as flash or with bravado. Barry, black cap upon his head, told Kelly “… the verdict pronounced by the jury is one which you must have fully expected no rational person would hesitate to arrive at any other conclusion but that the verdict is irresistible and that it is right.” Kelly, gazing at Barry said, “My mind is as easy as the mind of any man in this world.” Barry called him blasphemous: “… you appear to revel in the idea of having put men to death.” Kelly retorted “more men than me have put men to death” directed at Barry, notorious since the l850s for invoking the death penalty. This exchange continued on at length until Barry sentenced Kelly to death concluding with the words “… and may God have mercy upon your soul”. Kelly replied, “I will go a little further than that, I will meet you where I go.”

The curse had force. Barry died suddenly but 12 days after Kelly was hanged. Barry was an extraordinary man. As a barrister Barry was the first to appear for Aborigines without fee. Barry was instrumental in the establishment of the magnificent State Library of Victoria; he worked assiduously to establish Melbourne University and was its first Chancellor; he was responsible for the establishment of the Philosophical Institute and the Melbourne Hospital. He was a great man of public affairs.

Barry was also a Judge involved in the Eureka trials. The Eureka uprising looms large in Australian history, an uprising of miners on the Ballarat goldfields led by Irishman Peter Lalor. Lalor, also a Trinity graduate, trained as an engineer, his father a Member of Parliament, his family of the 7 septs of leix. That Lalor, vestige of old Irish aristocracy should have been a dig- ger at Ballarat says much for the solvent effect of immigration and the gold rushes.

To explain the Eureka uprising briefly is difficult. Rigid police enforcement of a licence fee, accompanied by manhunts, overnight chaining of delinquents to trees, police corruption, hard times on the goldfields and a mass of humanity meant discontent was high. In 1855 hundreds of diggers marched to Bakery Hill, Ballarat, and unfurled their flag, the flag of the Southern Cross. They burned gold licences. Two days later their stockade was overrun by troopers with over 20 killed.

Mark Twain described this action as a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a revolution small in size but great politically. Thirteen diggers were charged with high treason. Barry was one of three judges who heard a number of trials. Stawell (later Chief Justice) prosecuted. The prosecution chose the first to be tried carefully. An American black, Joseph, was the accused in the first trial. The Crown felt his race would be unpopular with the jury.

At this trial the first test of the legal process occurred when the Crown challenged jurors with Irish names together with publicans. The defence threw the courtroom into mirth when it objected to jurors who gave their occupations as gentlemen or merchants. Eventually two gentlemen and a publican got through. Joseph was acquitted. His acquittal was met with loud cheers from thousands who gathered outside the Court. There was even talk of storming the Court if a guilty verdict was delivered.

Even with long delays between trials and new jury lists, acquittal followed acquittal. The trials took on an air of farce.

In the last trial Barry solemnly warned the jury: “The eye of heaven was upon you and your verdict.” This jury deliberated for 20 minutes — the shortest deliberation of all the trials. Not one digger was found guilty. When Manning, Irishman and Eureka rebel, was freed outside the Court to a large throng he declared:

I owe my life to the unbending honesty and integrity of a Melbourne jury. Future history will remember these people with honour.

Ireland QC appeared for the defence in the Eureka trials. Ireland was also a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin (in 1837, the same year as Barry). It was said of Ireland that he was the greatest advocate the Victorian Bar had seen. He died a bankrupt and in poor circumstances, admitting he had squandered four for- tunes in his lifetime.

Lalor, the leader of the Eureka uprising, was wounded when the stockade was overrun. He managed to escape and eventually received a pardon. He was elected to the Victorian parliament in 1855.

I think in Victoria of all the Australian states the Irish links have been the closest. The Supreme Court of Victoria has a dome modelled on Dublin’s Four Courts. Until the developers’ cranes rendered it rubble, on the adjacent corner to the Supreme Court was the second home for generations of Melbourne barristers, the Four Courts Hotel, later to become Four Courts Chambers. In Victoria, and no other Australian state, as in the Irish courtroom, solicitors sit facing counsel with their back to the Judge.

In Victoria, Queen’s Counsel, and now Senior Counsel, wear with their gowns a rosette at the back. Popular belief held that the silks’ rosette was of Irish origin. Great was the disappointment of the correspondent of the Victorian Bar News who reported on the Australian Bar Association conference held in Dublin in 1988. The idea that the rosette was another tradition inherited from Ireland was a “furphy”.

Douglas Graham QC (a Scot) in the following edition of the Victorian Bar News seemingly obtained great satisfaction in revealing the rosette belonged with Windsor court dress and was otherwise known as a “wig bag” or “powder rosette”, that those who wore the rosette looked “rather as though they had just attended a levee and had forgotten to take it off”.

I digress. Victoria in 1851 became a Crown colony separate from New South Wales. From 1857 to 1935 every Victorian Chief Justice was Irish born; all bar one were graduates of Trinity College, Dublin.

The great Gavan-Duffy family has been the subject of a separate paper at this conference. Charles Gavan-Duffy declared himself the first emancipated Catholic in Ireland. Nevertheless, he left Ireland for the Victorian Bar. He was greeted on his arrival in Melbourne by a welcoming committee. He combined law and poli- tics. He became Premier of the State of Victoria. After the death of his second wife, he returned to Europe. In France he married Louise and had a further four children. Of those four children Frank became Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia and George, President of the High Court of Ireland. His grandson Charles Gavan-Duffy became a Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria and a great grandson Sir John Starke was a legendary Victorian barrister and a fine Justice of the Supreme Court.

Irish nationalism was a strong under- current of Australian politics, particularly in the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Barrister Gerard Supple came to Australia in 1857. He had been associated with the 1848 uprising in Ireland. He became a member of the Victorian Assembly. He was so angered by the anti Irish sentiment of The Age newspaper that in May 1870 he attempted to shoot the editor in broad daylight in La Trobe Street, Melbourne. Whether by accident or because he was almost blind he wounded the editor but killed a bystander.

When in the 1880s brothers John and William Redmond arrived in Australia to represent the Irish Parliamentary Party and the National Land League, tensions went up a notch. Hotels refused accommodation to the Redmonds, public halls were closed to them. So complete was the shut down of public halls in Melbourne that the Irish community set about build- ing the Hibernian Hall. In most areas the Redmonds’ visit produced enormous enthusiasm, particularly in country districts. In New South Wales at Temora John Redmond was met with a cavalcade of a thousand men on horseback.

Young Frank Gavan-Duffy, educated by the Jesuits at Stoneyhurst and at the University of Melbourne, was presented with a dilemma. In Melbourne the respect- able Irish ran for cover. Young Duffy turned up at the Redmonds’ meeting. Afraid of the damage associating with the Redmonds might do to his law practice, he spoke of the necessity of avoiding the introduction of Ireland’s problems to Australia. He pleased nobody.

Another great figure of Australian legal and political history took the stage that day. Henry Bourne Higgins felt he must bear the cost of witness to his beliefs. He vigorously supported home rule for Ireland.

Higgins was born in Ireland on 30 June 1851 in County Down, the second of nine children. His father was a Wesleyan preacher who decided to emigrate, send- ing his family ahead of him to Melbourne in 1870. After secondary education Higgins went to work but then won a university exhibition. He completed degrees in Arts and Law at Melbourne University. In 1876 he was called to the Bar in Victoria. His identification with the Redmonds did not do his political career any harm. In 1900 when he opposed the Boer War he lost his seat in Geelong but at the next election he won the seat of North Melbourne, obtaining the vote of a large Irish Catholic electorate.

In 1901 with the Federation of Australian states, the Commonwealth of Australia was born. Higgins in 1906 was appointed to the High Court. In 1907 Higgins was appointed to the Presidency of the Arbitration Court. He presided over the famous Harvester Judgment which declared a basic or minimum wage for working class Australians, a wage sufficient to provide food, water and shelter, a wage designed to allow employees to live in a condition of “reasonable and frugal comfort”.

Higgins was typically Irish — a contradiction — radical lawyer, a father of federation who opposed the constitution, upper middle class hero of the labour movement and protestant supporter of the Irish cause.

By the turn of the 20th century the nation was changing but lawyers a hundred years ago were no different to lawyers of today in that they liked the reminiscence.

In the Bulletin in 1913 a reminiscence of bush justice was published under the heading, “They never did it better in Ireland”:

In the 1850s things were done, in Victoria, in a free-and-easy, unconventional way. The writer remembers staying at Murphy’s Castlemaine Hotel when the sessions were on, and at the dinner-table, along with the judge on circuit, his associate, the Crown prosecutor, and a number of barristers, were several persons charged with criminal offences, but out on bail. Among these were two young men from Smythesdale, who were to take their trial for tarring and feathering a man. After dinner, at the suggestion of bibulous little barrister McDonough (known as John Phillpott Curran), the table was removed. Quinn, a surveyor, produced his fiddle, and soon was presented an astonishing spectacle, judge, men on the jury list, solicitors, barristers and offenders, whooping around the jib, and reel, and polka, and waltz, until the morning hours, when broiled bones and whisky-punch finished up the saturnalia.

Next day every jig fitted into its proper place. The people on bail gave themselves up. The judge sat. The Crown prosecutor thundered his charges against men with whom he had hobnobbed the night before. And the two young fellows, tried for tar- ring-and-feathering got three years’ “hard”. As G.V. Brooke (one of the company) observed, “They never did it better in Ireland.

Because I reside south of the Murray River I will only refer briefly to the Irish of New South Wales. In so doing I borrow very heavily from the words of Sir Gerard Brennan and a paper he delivered to a conference of the Australian Bar Association in Ireland in 1988.

Roger Therry was a Dublin man, whose father was one of the early Catholic barristers admitted to that profession when the penal laws were relaxed at the end of the 18th century. Therry went to Trinity College, Dublin. He was called to the English and Irish Bars. He was private secretary to Canning, and was subsequently appointed Commissioner of the Court of Requests in New South Wales. His was the tenth name on the roll of NSW barristers and he conducted a successful practice whilst discharging his duties in the Court of Requests.

Therry was joined in Sydney by a fellow student he had met at Trinity College, John Herbert Plunkett. Plunkett had been a successful barrister on the Connaught Circuit. Plunkett was appointed Solicitor- General for New South Wales. He arrived in Sydney in 1832. In 1836 he became Attorney-General.

Plunkett and Therry were men of integrity. In 1838 they prosecuted to conviction the perpetrators of the infamous Myall Creek massacre in which a large number of Aboriginals — men, women and children — were slaughtered. The rigorous enforcement of the law in protection of Aboriginal people excited a great deal of comment, but the Attorney-General and his junior counsel earned public respect for their impartial enforcement of the law. Plunkett secured the passage of the Church Act in 1926 which established legal equality between Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians — later extended to Methodists. He became President to the Legislative Council and was elected to the Legislative Assembly for a term. He was a noted leader of Catholic opinion, a supporter of Caroline Chisholm, a force in the establishment of St Vincent’s Hospital. He sat on the Wentworth Committee responsible for establishing of the University of Sydney and became its Vice-Chancellor. He died in Melbourne on his 67th birth- day.

Therry’s career followed a different course. He was appointed resident judge at Port Phillip. He was not received well by the Port Phillip community. From 1846 to 1859 he was a Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. In May 1850 he held the first circuit court for the district of Moreton Bay. After Therry retired he lived in Paris and London before return- ing to his native Dublin.

Sir James Martin and Sir Frederick Darley were Chief Justices of New South Wales. Both were born in Ireland. Martin arrived in Sydney in 1821 as a child aged

18 months. His parents were poor but made sacrifices to secure an education for a brilliant son. He became a barrister and Attorney-General. On two occasions he was Premier of the State. He became Chief Justice in 1873. He died in 1886 and was succeeded by Darley.

Darley was a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, a member of the Munster Circuit. He arrived in Sydney in 1862 and became Queen’s Counsel in l878. He never saw public recognition though he was laden with Honours. He desired to be remembered only as “an old Irish gentle- man”. He died in London in 1910 and was buried in the family vault at Dublin.

The Irish influence on the Australian profession has been enormous. That influence has changed. The Anglo-Irish as a group or class have fallen away. Irish Australian lawyers of the latter half of the 20th century were the grandchildren or great grandchildren of the Irish who left their homes in despair but with hope and above all a deep longing for freedom. When consideration is given to the names of some of the Judges of our High Court responsible for the Mabo judgments — a key judgment in relation to the rights to land of Aboriginal people, Brennan, Gaudron, McHugh, Toohey — I think one can say that that in Australia the Irish have passed on, through the generations, those hopes and that passion for freedom possessed by their forebears.