Kelly Country contained a wealth of characters that contributed to the making of the legend. From the people directly involved in the uprising, the hostages taken during the Gang’s numerous raids, the writers, politicians, police, and the general public who looked on with growing interest against the Gang’s blatant defiance towards British law, listed below are some of the more colourful figures, family and friends, associated with the Kelly Gang.

Ellen Kelly

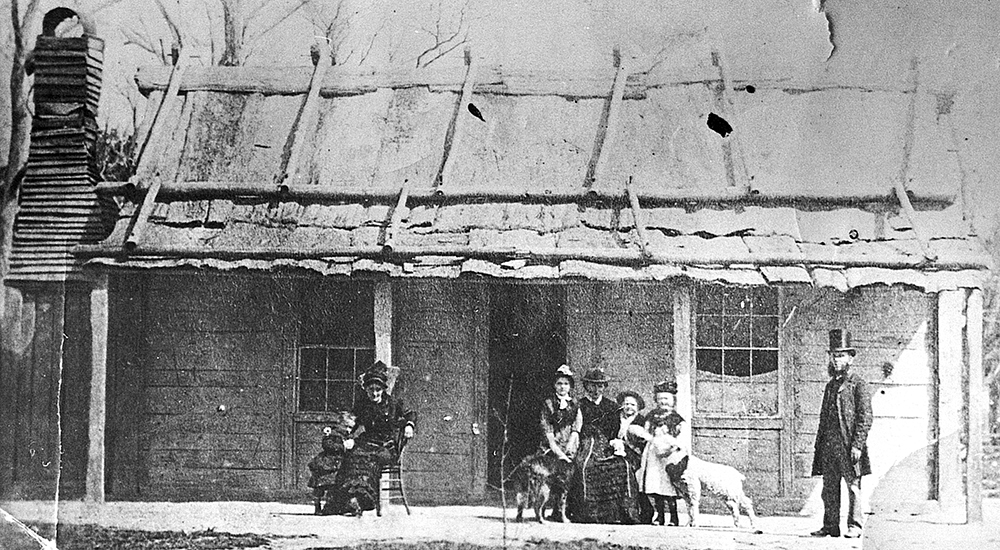

When Ellen Kelly died on 27 March 1923, she was age ninety-one. Ellen had outlived her two husbands and seven of her twelve children and reared three grandchildren after their mother died, including Frederick Foster, who was killed in France during World War One. In 1841, Ellen and her six brothers and sisters arrived in Australia from County Antrim, Ireland. Her father, James Quinn, was a free settler who rented land for dairying in Brunswick upon their arrival.

The family then moved up the Hume Highway to Broadmeadows. In the early 1850s they settled in Wallan but trouble with the law soon followed. In 1864 James Quinn decided to move his family once more, this time to Glenmore in the King Valley. In 1875 the Quinns sold their lease and selected land near Greta. At the same time the police presence in Greta increased dramatically.

A hand-tinted cartes des visite of Ellen Kelly photographed by W. Burman in Fitzroy in 1874, with his decorated details. Ellen Kelly had married George King in February 1874 and this photograph shows Ellen pregnant with the future John Kelly King.

A hand-tinted cartes des visite of Ellen Kelly photographed by W. Burman in Fitzroy in 1874, with his decorated details. Ellen Kelly had married George King in February 1874 and this photograph shows Ellen pregnant with the future John Kelly King.

Without denying the clan caused trouble, you would be hard pressed to justify such an increase in police numbers. They where involved in stock theft, not rape and murder. In later years, when the police employed spies to monitor the family’s movements, they were often referred to as ‘diseased stock’. The Kelly’s became part of the clan on November 18, 1850 when Ellen and John ‘Red’ Kelly eloped. They were married at St Francis’ Church, in Melbourne. The new Kelly family settled at Beveridge, near Wallan, and began raising a family. Jim Kelly, the second eldest son would comfort his mother through to her death. By 1860 the family had moved to Avenel, renting forty acres on the banks of the Hughes Creek. Dan was born here a year later and at the age of five he was listed as a suspected horse thief in the Police Gazette. Another example of police obsession. 1865 saw John ‘Red’ Kelly sentenced to six months gaol for the possession of a cowhide. By 1866 ‘Red’ was dead, having suffered from dropsy not long after being released from, what was to be, his final sentence. So, at the age of twelve, Ned had to leave school as he now found himself the man of the house.

Six months later, the Kelly family moved again, this time to an eighty-eight-acre selection near Greta. Ellen’s first court appearance happened not long after, when she was fined two pounds for abusing a neighbour. The land on the selection was of poor quality. However, the family hut was used as a stopping-off place for the Quinn clan. Police interest in the extended family grew, with the young Kelly boys being bought up on numerous stock charges. In one instance, twelve-year-old Ned and ten-year-old Dan were in jail for two days on horse stealing charges before the case was dismissed. Ellen had three charges dismissed by the magistrate over the following year, including selling sly grog and furious riding. Her son Jim was not so lucky, being sentenced at fourteen to five years gaol for stealing four cows.

It was high summer, 19 February, and Ned barely returned from Pentridge when his mother and George King were married in Benalla in the private home of the Rev. William Gould according to the rites of the Primitive Methodists. The witnesses were Ned himself and Margaret’s husband Bill. King no doubt – like all other new Australians before or since – had come to a new country because something had gone wrong in the old. He was not much older than Ned himself.

Max Brown

Australian Son

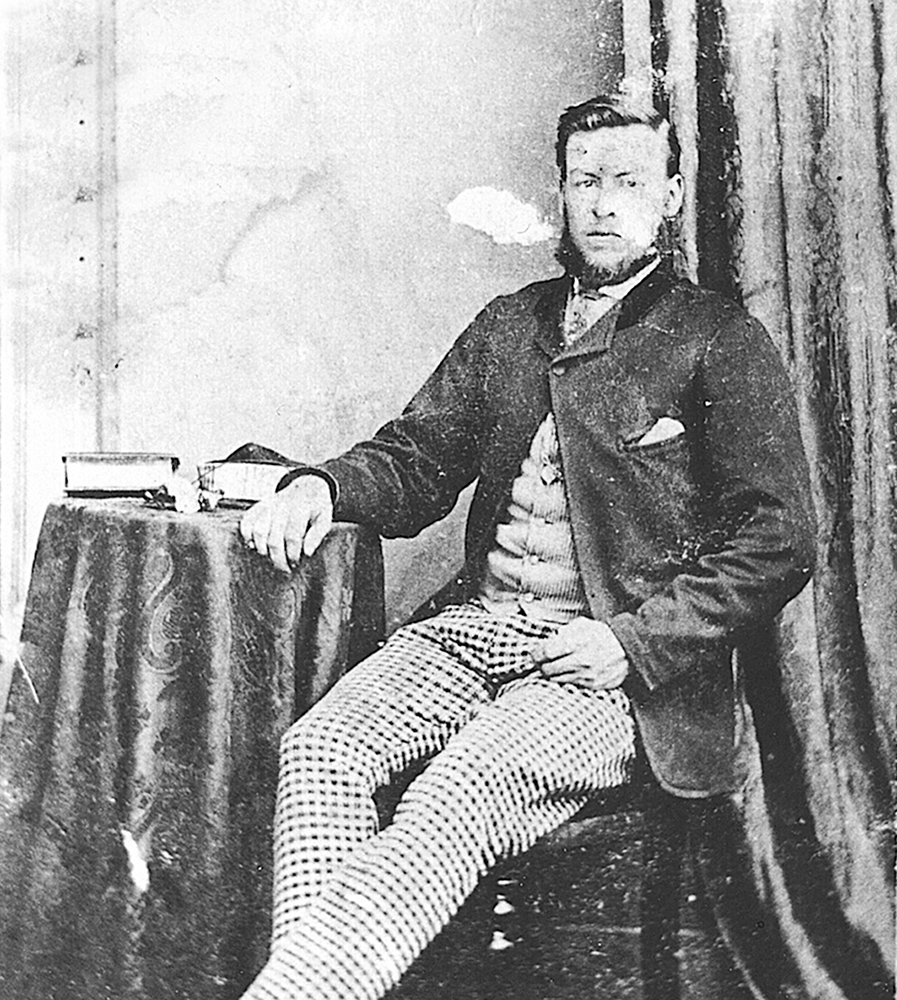

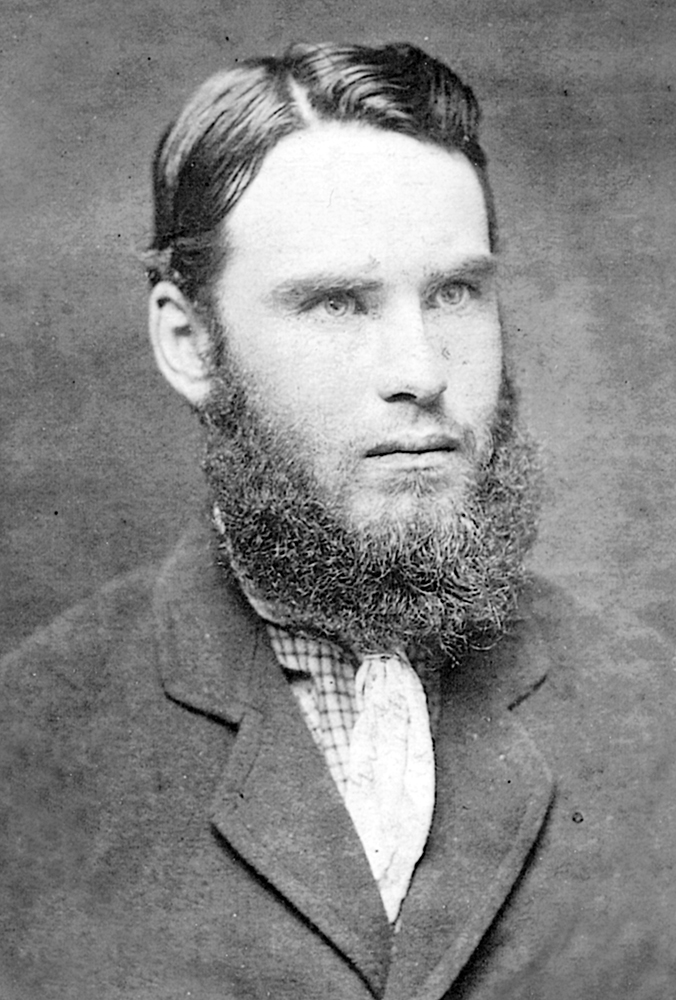

Ned’s American stepfather, George King, who married Ellen Kelly in 1874. They had three children, the last born only two days before the Fitzpatrick incident, which sparked the Kelly outbreak. King disappeared in 1877-78 after a major horse-stealing exploit with Ned. It’s possible he may have met with foul play as King was known to be a perpetrator of domestic violence, something the Kelly boys and their friends would have found intolerable. Shortly afterwards, Ellen resumed the surname of Kelly, which was also adopted by King’s three children. Image: Max Brown

On February 19, 1874 Ellen married a Californian named George King. She had three children by him, including baby Alice whom she took to gaol after the Fitzpatrick incident, before Mr King disappeared in 1878. April of the same year saw a warrant issued for the arrest of Dan on suspicion of horse stealing. This lead to the Fitzpatrick affair, the turning point in the Kelly saga. When the year came to a close Ellen King, mother of twelve, was in gaol for attempted murder, three police were dead and Ned and Dan were outlaws.

By the time she was finally released in 1881 the uprising had come and gone. The police and citizens of Victoria’s North East would never be the same again. As for Ellen, she would never to return the gaol. Instead she headed back to her selection where she finally qualified for ownership in 1893. When she died she was a woman of dignity, admired and respected by the people around her. Publicly she refused to discuss her sons, however amongst friends she was heard to say she was proud of them. She thought Dan was the better general, yet she likened Ned to Napoleon.

John 'Red' Kelly

John Kelly was baptised on 20th February 1820 in Moyglass Church in Tipperary, Ireland. His parents, Thomas Kelly and Mary Cody, lived near the town of Clonbrogan, which is about one mile west of Moyglass, and raised a family of five boys and two girls on less than half an acre. While six of the children would make the journey to Australia, it was the eldest son, John, who made the first crossing thanks to a sentence of seven years of transportation.

Kelly had worked as a ranger on Lord Ormonde’s Killarney estate until transported for stealing two pigs. The pig, known variously as His Lordship (because the landlord was English) or Georgie (after George IV), was bought at market as a piglet, then fattened and sold and commonly called ‘the gentleman who pays the rent’. Eight out of every ten Irish convicts were transported for larceny of an animal.

Kelly had made the voyage to the Derwent in the barque Prince Regent and done time with the bushranger William Westwood, hanged with ten other convicts on Norfolk Island for organising a mutiny. Like Red himself, Westwood had been a harmless short-sentence man before absconding from a sheep run south of Sydney. According to tradition, Red was run-of-the-mill Irish but generous to a fault. He could sign his name, but it is doubtful if he could write much – hardly surprising since whatever common schools Ireland had were conducted clandestinely under hedgerows.

Max Brown

Australian Son

Red Kelly, as he was called for his reddish hair, had not long completed his seven-year sentence across the strait in Tasmania. Around 1849, Ellen Quinn’s father, James, came to know John Kelly, a fellow countryman post-splitting on Merri Creek. In 1850, he met Ellen Quinn, and they were married on 18 November that same year in St. Francis’s Church, Melbourne. Red made a hard living for the next fifteen years from horse dealing, gold mining and dairy farming. Over this period of time, Red was to father eight children – including Ned. In 1865, he was charged with stealing a calf from Mr. Morgan. While the charge of cattle stealing was dismissed, the charge of ‘unlawful possession of a hide’ was upheld, and he was fined £25 or six months in gaol. Unable to pay the fine, Red spent many long months locked away.

Released in an unhealthy state, by November 1866, Red’s constitution had seriously deteriorated — helped along by his penchant for the bottle. At forty-six, John Kelly finally succumbed to the effects of dropsy on 27 December 1866. His death was reported and signed by his son Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly, who, while not yet twelve years of age, was to take over as the man of the house. Red was buried in Avenel Cemetery, Victoria, on 29 December 1866.

Tom Lloyd Junior

While her husband, William Skilling, was in prison, serving six years of hard labour, Ned’s sister Margaret began a relationship with Tom Lloyd that would culminate in a marriage and a family of eleven children. During the final hours of the Glenrowan battle, Tom comforted Ned when he could have escaped with Lloyd’s help, but predictably, Kelly refused. When Tom visits Ned in prison before his hanging, Kelly tells him where to find a planted saddle. It highlights the bond these two bushmen shared. Later, Tom became a respected farmer and lived into his seventies. When Tom passed away in 1927, he was buried at the Greta Cemetery.

Tom Lloyd, cousin of the Kelly boys, arrived just after the fatal gunfight. He was to prove their most loyal and active supporter. Image: Victoria Police Historical Unit

Tom Lloyd, cousin of the Kelly boys, arrived just after the fatal gunfight. He was to prove their most loyal and active supporter. Image: Victoria Police Historical Unit

Jack Lloyd’s son, Tom Junior, was possibly closer to Ned than any of the other members of the gang. Being Ned’s first cousin, Tom was a staunch supporter, often called the fifth member of the Kelly Gang. He is recognised today as an important piece of the Kelly puzzle. Tom was a friend, adviser, strategist, and tactician to the Gang.

Don’t ride into this mess.

Ned to Tom

The Last Outlaw

During the Kelly uprising, he was a formidable leader of the sympathisers, which led to his arrest. It has been said that in other circumstances, he could have been Ned Kelly. Tom and Wild were mainstays of the Kelly Gang, but where Isaiah ‘Wild’ Wright was arrogant, Lloyd was far more close-chested.

Jim Kelly

Jim Kelly first came to the attention of the constabulary when Constable Hall’s successor, Constable Flood, targeted the then twelve-year-old, who was working for a hawker, and his younger brother Dan, still at Common School in Greta. The boys were caught illegally using the hawker’s horse and locked up for two days.

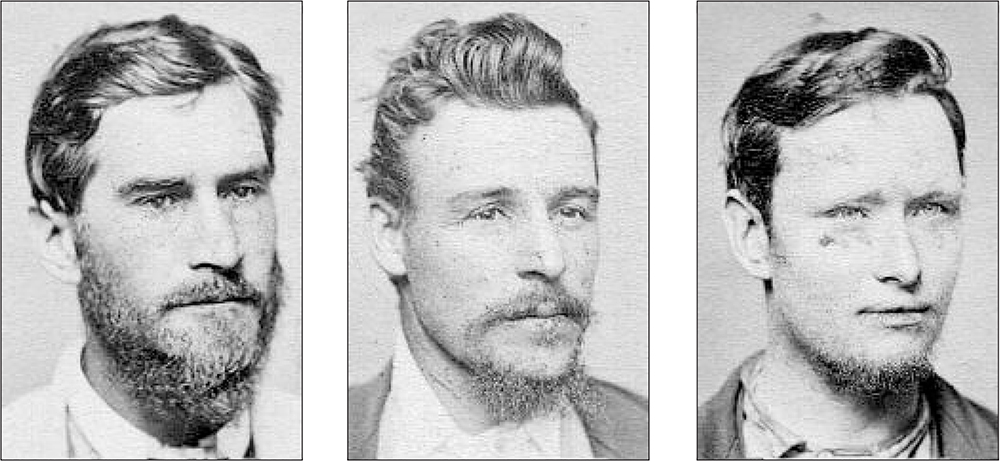

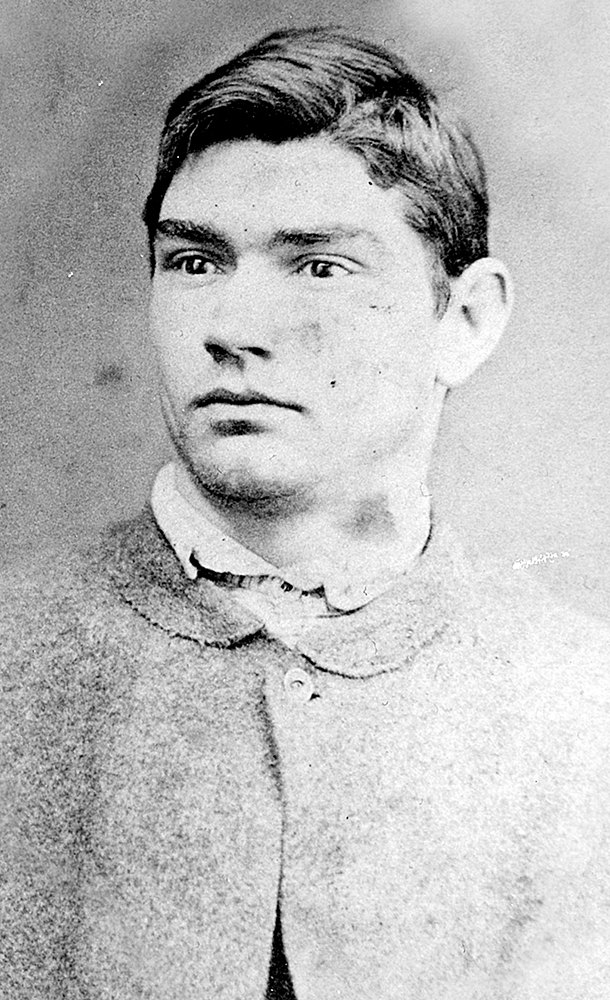

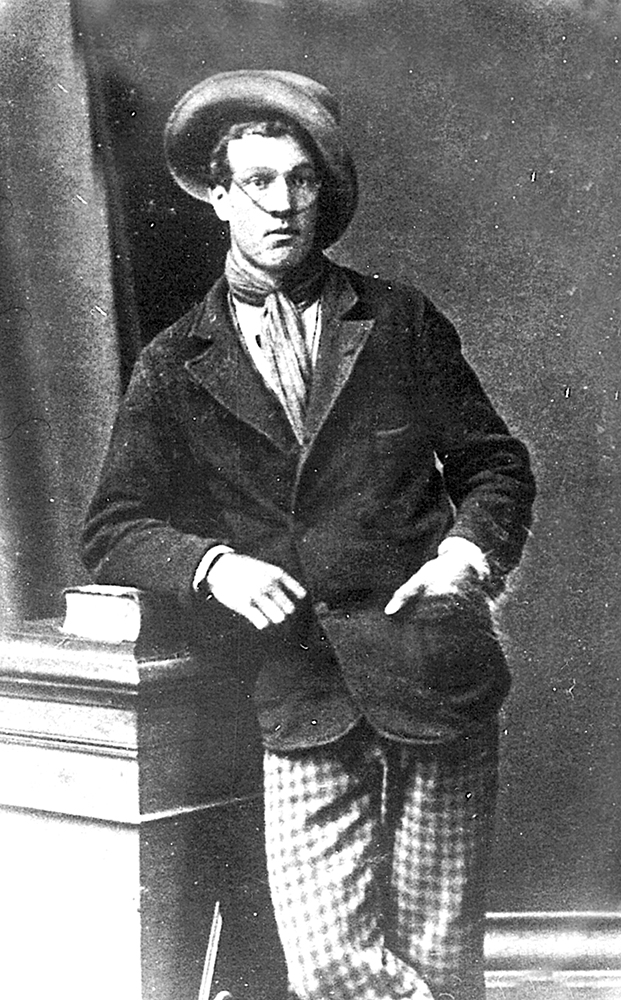

Jim Kelly, four years Ned’s junior, was serving a three-year sentence for horse stealing when his brothers were outlawed and was not released until January 1880. The gaol term probably saved his life. Image: Max Brown

Jim Kelly, four years Ned’s junior, was serving a three-year sentence for horse stealing when his brothers were outlawed and was not released until January 1880. The gaol term probably saved his life. Image: Max Brown

In February 1873, John Lloyd – the same man who had put Harry Power away – was convicted of maliciously killing a horse. To raise money for his defence, his brother Tom Lloyd got Jim Kelly, aged fourteen, and a sixteen-year-old named Williams to sell some stray cows. Both boys were arrested, charged and gaoled for five years each. Ned was determined that the injustice done to his brother Jim would not be repeated on his brother Dan, who was arrested for stealing a saddle and bridle after a trip to Benalla with his teenage mates. This time, Ned hired a lawyer, and Dan was subsequently acquitted with the help of a receipt and the help of his mates’ witnesses.

It is not over yet.

Jim addressing the Bourke Street crowd

November 1880

Already eighteen and as tall as Ned, Jim Kelly came out of Beechworth, having been given a year’s remission for good behaviour. He had the good fortune to leave the district with some of his mates – their aim was to strike a blow with the blade in the Riverina sheds, some of which had forty or fifty stands. However, by June 1877, Jim had been arrested and convicted of horse theft. Four years Ned’s junior, Jim Kelly, was sentenced to three years in prison. He was behind bars when his brothers were declared outlaws, and he was not released until January 1880. Jim returned to Greta to be with his mother, Ellen, and surviving siblings. In later years, he worked as a bootmaker and became a respected member of the local community, living until the ripe old age of eighty-nine. He was buried at Greta Cemetery on 18 December 1946, on the same day he died. Author of Australian Son, Max Brown, attributes the 1877 gaol term to Jim Kelly’s longevity.

Harry Power

Harry Power was born Henry Johnson in Waterford, Ireland, in 1819. He and his family migrated to England in the 1830s, where he worked as a piecer at the Woolen Mills in Ashton, Lancashire. He was sentenced to seven years of transportation for stealing shoes in 1840. He arrived in Tasmania in May 1842. By 1847, Henry Johnson received a ticket of leave, so he travelled to the mainland, where he worked as a horse dealer in Geelong and Maryborough.

Harry Power was already middle-aged when he escaped from Pentridge in February 1869 and launched a spectacular fifteen-month bushranging career. Image: Max Brown

Harry Power was already middle-aged when he escaped from Pentridge in February 1869 and launched a spectacular fifteen-month bushranging career. Image: Max Brown

In 1855, he received a thirteen-year sentence for horse stealing and shooting a police trooper. During his stint, Power served time in various prisons, including aboard the prison hulk ‘Success’ anchored off Williamstown in Hobson’s Bay. Released in 1862 and now under the name of Harry Power, he was posted ‘illegally at large’ after ignoring his conditions of release. Subsequently, a reward was placed on his head. Harry moved northeast of Victoria, where in 1864, he was arrested for horse stealing and sentenced at Beechworth Courthouse to seven years imprisonment at Pentridge Prison in Coburg.

In 1869, only a few months before he was to be released, Power escaped by hiding in a hole in a new section of prison wall. He then returned to North East Victoria where he was responsible for a spate of armed robberies of travellers, coaches and horses. His territory ranged from Kyneton to Bairnsdale, across the Divide and deep into Gippsland and, and up to southern New South Wales. He once held up the Mansfield-Jamieson coach twice in a week.

While roaming the Great district, Power became friends with the Kellys, Lloyds and Quinns and often stayed with the families. It was here that Harry Power became known as the ‘Gentleman Bushranger’. Many of Power’s victims reported seeing a ‘young man’ in the background during the bail-ups. This young man was to learn a great deal about bushmanship during his brief liason with the gruff old bushranger. For the young man was Ned Kelly, and the lessons learnt would stay with him during his short life. Harry Power was made famous by being credited with tutoring a young Ned Kelly in the ways of bushranging during 1870. It was a brief affair, one where Ned made only five pounds and which nearly cost him his life. Ned was arrested as Harry’s accomplice in May 1870. However, the charge was later dismissed.

I will teach you things you would pay guineas to learn! Give attention to me, Ned, and I will reveal to you every secret of me daring trade.

Power to young Ned

The Last Outlaw

Wet weather had prevented the Quinn’s peacock from giving the danger signal and police captured Harry Power asleep in his hide-out on a rise behind the Quinn homestead ‘Glenmore’, near Whitfield. Initially Ned Kelly was blamed for Power’s capture but it was later revealed his uncle, a long time friend of Harry’s, Jack Lloyd had lead police to the bushrangers camp and pocketed 500 pounds for his trouble. For the charge of three armed robberies (although he probably committed more than ninety offences while at large) Power was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment with hard labour to be served at Pentridge.

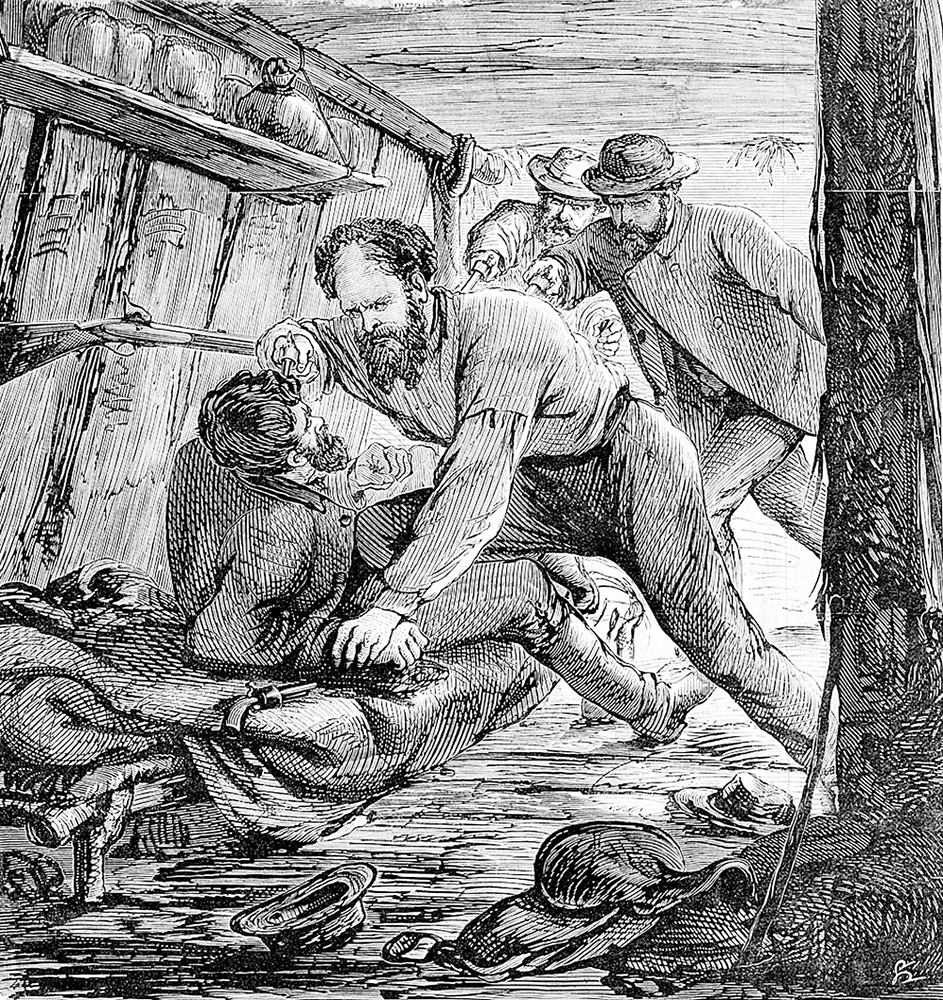

Harry Power’s capture, surprised at dawn in his mountain hideout. Superintendent Nicolson grapples with him while Superintendent Hare and Sergeant Montfort close in. Harry believed that Ned had betrayed him. Image: Max Brown

Harry Power’s capture, surprised at dawn in his mountain hideout. Superintendent Nicolson grapples with him while Superintendent Hare and Sergeant Montfort close in. Harry believed that Ned had betrayed him. Image: Max Brown

Harry Power survived his prison term, being released in 1885, an old and sick man. For a period afterwards he acted as a tour guide aboard the hulk ‘Success’ under the title ‘The last of the Bushrangers’. In 1891 Power made his last trip to the North East where it was reported he slipped and drowned whilst fishing in the Murray River near Swan Hill. He survived his famous apprentice by eleven years. Mrs Kelly may have been half right when she called him a ‘brown paper bushranger’ but his death signified the end to the ‘Golden Days of Bushranging’ for Victoria’s North East.

Isaiah 'Wild' Wright

Arriving in Australia aboard the ‘Carlton’ in 1858 at the age of nine, Isaiah Wright was to become one of the Kelly Gang’s most staunch supporters. He moved to the Mansfield district when he was in his twenties and married Bridget Lloyd, a member of the Lloyd family and closely linked to the Kelly’s. March 1871 would see Ned become involved in a situation of Wright’s doing.

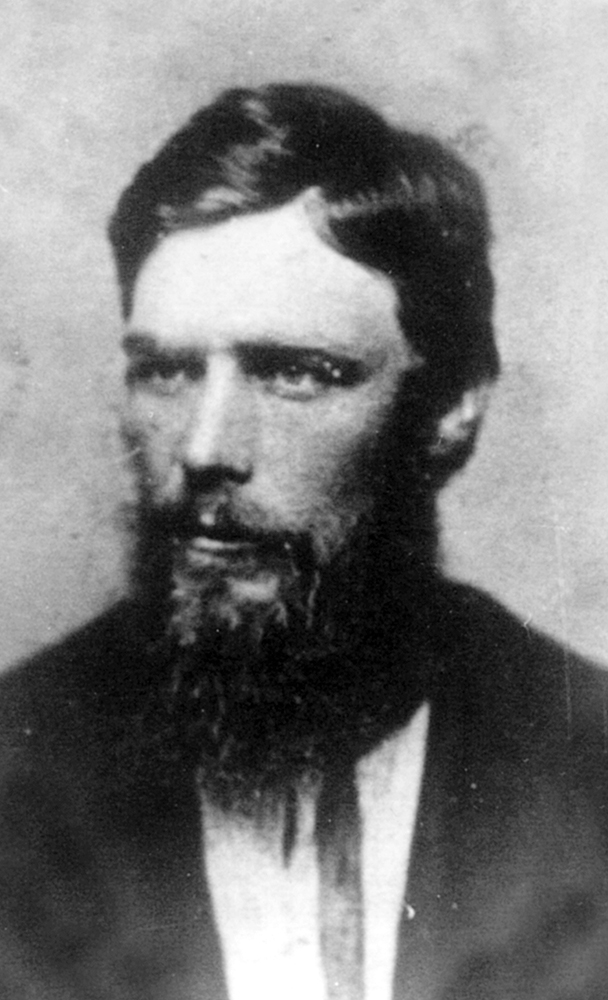

Isaiah ‘Wild’ Wright, a flamboyant young Mansfield identity who lost a horse while at the Kelly homestead and failed to tell Ned Kelly that it was stolen. Ned found the horse and rode it past the Greta Police Station to earn a brutal pistol-whipping from the local trooper, who had initially tried to shoot him. Ned was sentenced to three years hard labour. Image: Max Brown

Isaiah ‘Wild’ Wright, a flamboyant young Mansfield identity who lost a horse while at the Kelly homestead and failed to tell Ned Kelly that it was stolen. Ned found the horse and rode it past the Greta Police Station to earn a brutal pistol-whipping from the local trooper, who had initially tried to shoot him. Ned was sentenced to three years hard labour. Image: Max Brown

During a stay at Ellen’s, Wright said he lost a horse so he borrowed one from Ned and said if he found his they would exchange it when he called in from Mansfield again. What Wild failed to tell Ned was that his lost horse was stolen. Ned did find the horse but while riding it through Greta he was stopped by the sixteen stone thug Senior Constable Hall who arrested Ned for possession of a stolen horse.

Hall dragged sixteen year old Ned off the horse but could not hold him so he aimed his revolver at Ned’s head and pulled the trigger three times. A fight followed and Ned appeared to be winning until Hall got help. He then pistol whipped the boy shockingly. Later Hall admitted to hitting Ned four or five times ‘as hard as I could’.

Ned came home from Beechworth in March to find Alex Gunn, Annie’s husband, in the company of a tall, softly spoken horsebreaker, Isaiah Wright, of Mansfield. Known otherwise as Wild Wright, the visitor was in a fix because the chestnut mare he was riding had strayed, so Ned loaned him a mount. The missing mare was of distinctive appearance having a white blaze and docked tail. Ned found her, rode her into Wangaratta and loaned her to the publican’s daughters to ride around the town. This, he suggested, was proof he had no knowledge that the mare had been lifted from Maindample Park Station.

Max Brown

Australian Son

In 1871 Ned, Isaiah, and Alex Gunn (Ned’s brother-in-law) were sentenced at the Beechworth Courthouse. Ned and Alex got three years while Wild, who actually stole the horse, received only eighteen months. Perhaps to settle the score, or just to stage a sporting event, a bare-knuckled fight was organised for 8 August 1874. Wild, a big heavy man even taller than Ned, went twenty rounds but eventually succumbed to Kelly’s fists. They would however remain in constant contact. During the Kelly outbreak, Wild would assist the Kelly family by any means he could.

In Mansfield Wild rode past the police lock-up and yelled ‘Dogs! Curs! Cowards! Follow me if you want to catch the Kellys, I’m going to join the Gang. Come out a little way and I’ll shoot the lot of you!’

The following years saw Wild continue to be in trouble with the law, serving yet more prison years aboard the hulk ‘Sacramento’, and at Beechworth or Pentridge. During his term, Wild’s records show he was a constant thorn in the side of authority. In 1877 he returned to Kelly country and became a known Kelly sympathiser and active assistant, openly defying the police. He was present at the destruction of the Gang in Glenrowan, being one of the family who claimed the remains of Steve and Dan. Wild maintained a high profile during the following court events to the point where he was refused admission to see Kelly at the Melbourne Gaol prior to Ned’s execution.

Aaron Sherritt

When telling Kelly’s story, Aaron Sherritt is an enigma. He is first introduced to the main cast of characters through Joe Byrne, the man who would eventually shoot him dead. This action would pre-empt the showdown at Glenrowan, where Byrne, too, would forfeit his life.

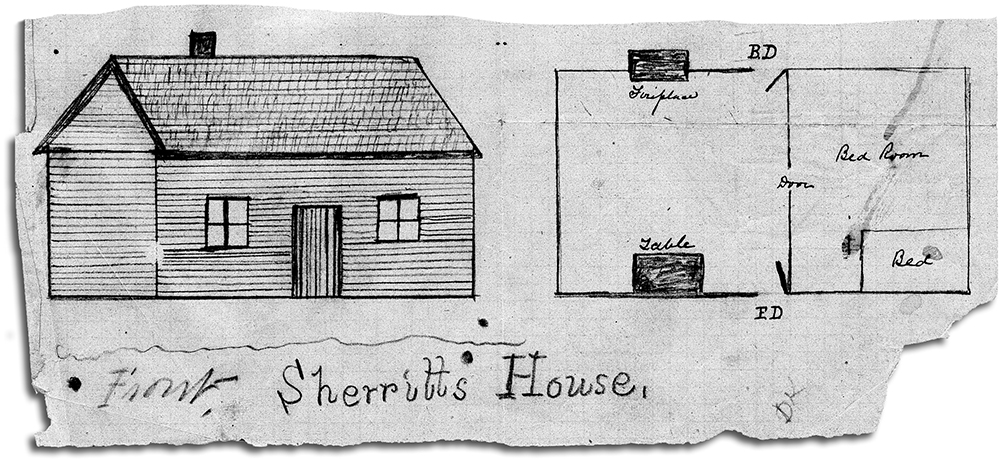

A member of the ‘Greta Mob’ reputed to be Aaron Sherritt, who became the key to Ned Kelly’s strategy to establish a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria. When Joe Byrne decided to kill his lifelong friend, the murder was planned to draw police into a trap. Image: Victoria Police Historical Unit

A member of the ‘Greta Mob’ reputed to be Aaron Sherritt, who became the key to Ned Kelly’s strategy to establish a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria. When Joe Byrne decided to kill his lifelong friend, the murder was planned to draw police into a trap. Image: Victoria Police Historical Unit

Aaron would be buried around the same time as his lifelong friend Joe Byrne. Sherritt was a Woolshed lad. He went to school with Byrne and they would later serve six months together for the unlawful possession of meat. As a close companion of Byrne’s, Sherritt was a regular visitor to Kelly’s Bullock Creek hideout.

After spending six months of 1876 in Beechworth for possession of stolen meat, Joe and Aaron were charged the following January with injuring a Chinese digger who surprised them diving into a dam near his camp. Aaron had thrown a rock at him and he’d been admitted to Ovens District Hospital.

Max Brown

Australian Son

Had Sherritt been in camp when the boys came across the police at Stringybark Creek, he would have become an unwitting member of the outlawed gang. Standing nearly six foot, the powerfully built Aaron was a fine bushman. His bush craft and horse riding abilities rivalled those of Ned Kelly himself. When visiting the police lookout over the Byrne’s hut Aaron would spend the cold winter nights without blankets or bedding. On one occasion, Superintendent Frank Hare wrote:

He was a man of most wonderful endurance. He would go night after night without sleep in the coldest nights in winter. He would be under a tree without a particle of blanket of any sorts in his shirt sleeves whilst my men were all lying wrapt in furs in the middle of winter.

Aaron Sherritt inadvertently implicated Joe Byrne as a Kelly Gang member when, on being asked to become an police informer, said he would consider the deal if Byrne’s life was spared. Even when others were branding Aaron a police informer, Kelly tolerated Byrne’s relationship with Sherritt because he saw Joe as a wise, patient sort of fellow. All this bravado, however, did not prevent Joe Byrne from murdering his one time best friend Aaron Sherritt.

Aaron was heard to remark to a senior Victorian police officer, ‘Ned Kelly could beat me into fits. I can beat all the others; I am a better man than Joe Byrne, and I am better than Dan Kelly, and I am a better man than Steve Hart. I can lick these two youngsters into fits. I have always beaten Joe, but I look upon Ned Kelly as an extraordinary man, there is no man in the world like him – he is superhuman. I look on him as invulnerable; you can do nothing with him.’

The greatest single tragedy of the Kelly story was Detective Ward’s ruthless, amoral, appalling campaign to incriminate Aaron in the eyes of the gang. The fact that it worked was a tragedy, and it was a tragedy that destroyed the gang.

Ian Jones

Rightly or wrongly, Joe believes Aaron to be a police informer. He certainly believed Sherritt betrayed him. History, however, is yet to prove that Sherritt supplied any real information that aided the police hunt. More than likely, Sherritt was trying to line his pockets with some easy money while attempting to throw the scent off the real trial. What is certain is that Sherritt made the fatal mistake of not letting Joe Byrne and the rest of the Gang in on his plan.