Double Jeopardy

There was a legal precedent known as autrefois convict and autrefois attaint which basically meant that since Ned Kelly had been declared an outlaw, he had already been found guilty for his crimes and could not be tried again in a court of law. Although, if Ned’s lawyer Henry Bindon (who was one of the most inexperienced junior barristers in the colony) had argued that point and the jury had acquitted him, Ned Kelly could still have been executed, because he had already been convicted under the outlawry charge. Note: The official meaning of double jeopardy is a procedural defence that prevents an accused person from being tried again on the same (or similar) charges following a valid acquittal or conviction.

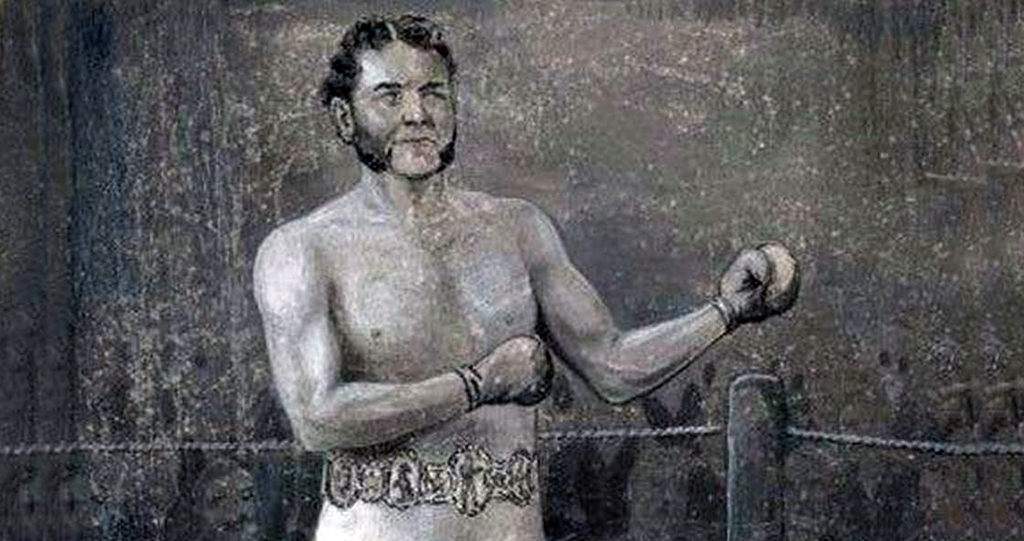

the north-east Victorian boxing champ met the Australian champ

Australia’s godfather of boxing was a man named Larry Foley. He once walked fifteen miles through swampland in the pouring rain to get to a bare-knuckle fight and proceed to knock out his opponent after thirty ‘short’ minutes (in the bare knuckle days some bouts went for hours and sometimes days). His most famous fight was in Echuca during 1879 when he pulverised American pugilist Abe Hickin who, the Riverina Herald described after the encounter as a man who, ‘presented a horrible sight. Both eyes were nearly closed, his lips were cut and blistered, his nose knocked out of shape, and his whole face pounded almost to jelly.’ Quite fittingly, Foley was crowned Australian champion. Stepping from the ring he was congratulated by a tall bearded man who introduced himself as north-east Victoria’s boxing champion – Ned Kelly. Foley went on to build the White Horse Hotel and set up the world renowned Australian Academy of Boxing.

Ned inspired soldier based armour in the First World War

The Kelly Gang’s crude armour holds a unique legacy. While best known for his Sherlock Holmes book series, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was also a doctor. During the early stages of the First World War Doyle pleaded and partitioned the War Office in London for ‘Kelly Armour’ to protect the troops. In advocating artificial protection for British soldiers Doyle announced, ‘When Ned Kelly walked unharmed before the Victorian police rifles in his own hand-made armour he was an object-lesson to the world. If an outlaw could do it, why not a soldier?’ In a press interview Doyle called Kelly in his armour ‘an object lesson to the world.’ He believed, ‘The use of armour is possible for the protection of the vital parts of a soldier’s body, and ought to be supplied to stormers, whose business is to cross “no man’s land”, attack the machine-gunners, and clear the way for the infantry.’ Doyle estimated that ninety per cent of the casualties sustained by the British on the Somme were due to bullets and shrapnel. While a number of British officers recognised that many casualties could be avoided if effective armour were made available, the British Army did not officially adopt Doyle’s recommendations. Instead many families, motivated by Doyle’s plea, employed blacksmiths to build protection for their boys. The idea of the Kelly Gang’s armour inspired, and saved, hundreds if not thousands of soldiers fighting on the Western Front and other theatres of conflict.

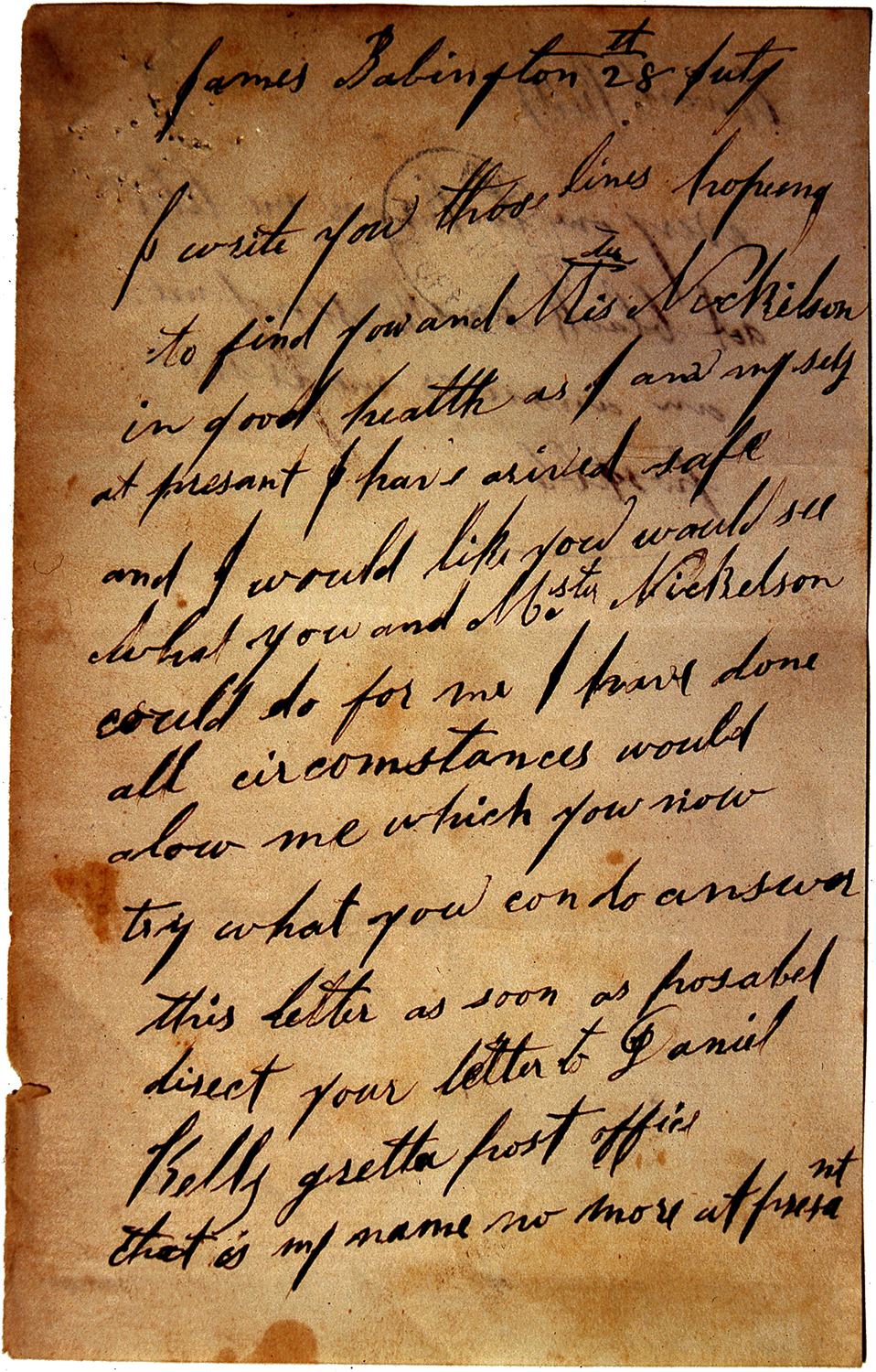

When Ned was fifteen he wrote a letter to a policeman

Ned Kelly was arrested for highway robbery in 1870, and narrowly escaped conviction. Soon after, Harry Power, who was betrayed by one of Ned’s uncles, was captured, tried, and sentenced to fifteen years gaol. Young Ned was blamed for the treachery and sought assistance from a policeman who had showed him kindness while he was on remand in Kyneton. This is what Ned wrote, ‘James Babington 28th July. I write those lines hoping to find you and Mister Nickilson in good health as I am myself at present I have arrived safe and I would like you would see what you and Mstr Nickelson could do for me I have done all circomstances would alow me which you now try what you can do answer this letter as soon as posabel direct your letter to Daniel Kelly gretta post office that is my name no more at present. Edward Kelly. every one looks on me like a A black snake send me an answer me as soon posable.’ It is not known if Sergeant Babington ever responded to young Ned’s plea for help.

Ned Kelly was arrested for highway robbery in 1870, and narrowly escaped conviction. Soon after, Harry Power, who was betrayed by one of Ned’s uncles, was captured, tried, and sentenced to fifteen years gaol. Young Ned was blamed for the treachery and sought assistance from a policeman who had showed him kindness while he was on remand in Kyneton. This is what Ned wrote, ‘James Babington 28th July. I write those lines hoping to find you and Mister Nickilson in good health as I am myself at present I have arrived safe and I would like you would see what you and Mstr Nickelson could do for me I have done all circomstances would alow me which you now try what you can do answer this letter as soon as posabel direct your letter to Daniel Kelly gretta post office that is my name no more at present. Edward Kelly. every one looks on me like a A black snake send me an answer me as soon posable.’ It is not known if Sergeant Babington ever responded to young Ned’s plea for help.

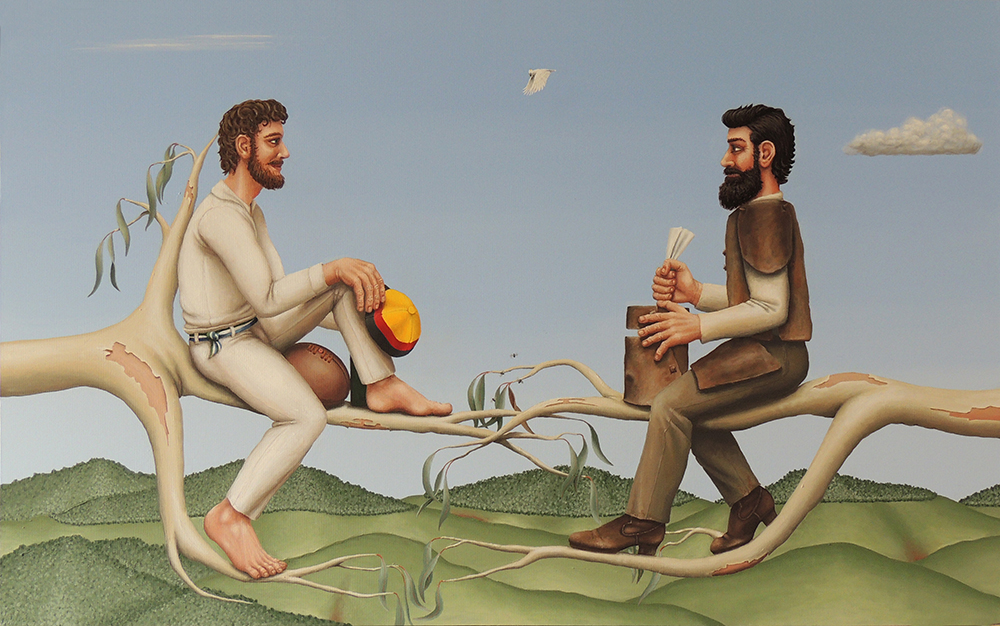

Ned has a connection to Australian rules football

Former Essendon football club team member Ian ‘Bluey’ Shelton was a champion centre half-back footballer for the Bombers in ninety-one games, including the 1962 and 1965 VFL premierships. In 1865, Bluey Shelton’s grandfather, Richard ‘Dick’ Shelton, was aged only seven when he slipped and fell into the flooded waters of Hughes Creek while on his way to school in Avenel. He was rescued by Ned Kelly, who was aged ten at the time. Ned jumped into the water fully clothed and dragged young Dick to safety. In an interview with the AFL’s Ben Collins, Bluey Shelton said, ‘If Ned Kelly didn’t do what he did, who knows? My grandfather might still have been able to get out by himself. But then again, he might not have. It’s a big part of our family history because my grandfather ended up having twelve kids, including my father.’ Two other Sheltons also played Australian rules football. One was Bluey’s uncle Jack, who was Richard’s son. He played twenty-eight games for St Kilda during the 1926 to 1929 seasons and played a further seven games for South Melbourne (now the Sydney Swans) in 1930. Jack’s son William Shelton, Bluey’s cousin, played twelve games for Hawthorn between 1957 and 1958.

Ned’s prized possession was a green sash

The green silk sash with a gold bullion fringe that was presented to Ned in 1865 by a grateful Shelton family for saving the life of their young son Richard became one of Kelly’s most treasured possessions. He wore it as a cummerbund during his last stand at Glenrowan. After Ned’s capture, Dr Nicholson of Benalla removed the sash while treating Ned’s wounds and kept it as a souvenir. Today, it is on public display in Benalla, still stained with Ned’s blood.

The green silk sash with a gold bullion fringe that was presented to Ned in 1865 by a grateful Shelton family for saving the life of their young son Richard became one of Kelly’s most treasured possessions. He wore it as a cummerbund during his last stand at Glenrowan. After Ned’s capture, Dr Nicholson of Benalla removed the sash while treating Ned’s wounds and kept it as a souvenir. Today, it is on public display in Benalla, still stained with Ned’s blood.

Australia’s greatest soldier claimed he once met Ned Kelly

Most historians agree that the tale below didn’t take place. But all agree Monash was a wry character who knew a story about meeting Ned Kelly would help endear him to the tens of thousands of soldiers he commanded on the battlefields across the Western Front.

It was February 1879, and the scene was the Kelly Gang’s robbery of Jerilderie’s Bank of New South Wales. One unnoticed spectator on that Monday was a Jerilderie storekeeper’s son on the last day of Christmas holidays from Scotch College in Melbourne. The storekeeper was Mr Louis Monash, his son was John. In the next century General Sir John Monash became one of Australia’s greatest statesman and it’s most distinguished military commander. In May 1918, during the First World War, he became commander of the Australian Corps – at the time the largest corps on the Western Front. The successful Allied attack at the Battle of Amiens on August 8, 1918, which expedited the end of the war, was planned and spearheaded under Monash. According to British historian A.J.P. Taylor, Monash was ‘the only general of creative originality produced by the First World War.’ Looking back through fifty remarkable years, Monash told a journalist that, as a small boy of thirteen, he sat on his father’s verandah while the outlaws collected their prisoners. The reporter wrote, ‘Sir John says that he has never been so overawed in his life as when the redoubtable bushranger spoke a few words to him, and for many a month he was the envied hero of his school as “the boy who talked to Ned Kelly”.’

It was February 1879, and the scene was the Kelly Gang’s robbery of Jerilderie’s Bank of New South Wales. One unnoticed spectator on that Monday was a Jerilderie storekeeper’s son on the last day of Christmas holidays from Scotch College in Melbourne. The storekeeper was Mr Louis Monash, his son was John. In the next century General Sir John Monash became one of Australia’s greatest statesman and it’s most distinguished military commander. In May 1918, during the First World War, he became commander of the Australian Corps – at the time the largest corps on the Western Front. The successful Allied attack at the Battle of Amiens on August 8, 1918, which expedited the end of the war, was planned and spearheaded under Monash. According to British historian A.J.P. Taylor, Monash was ‘the only general of creative originality produced by the First World War.’ Looking back through fifty remarkable years, Monash told a journalist that, as a small boy of thirteen, he sat on his father’s verandah while the outlaws collected their prisoners. The reporter wrote, ‘Sir John says that he has never been so overawed in his life as when the redoubtable bushranger spoke a few words to him, and for many a month he was the envied hero of his school as “the boy who talked to Ned Kelly”.’

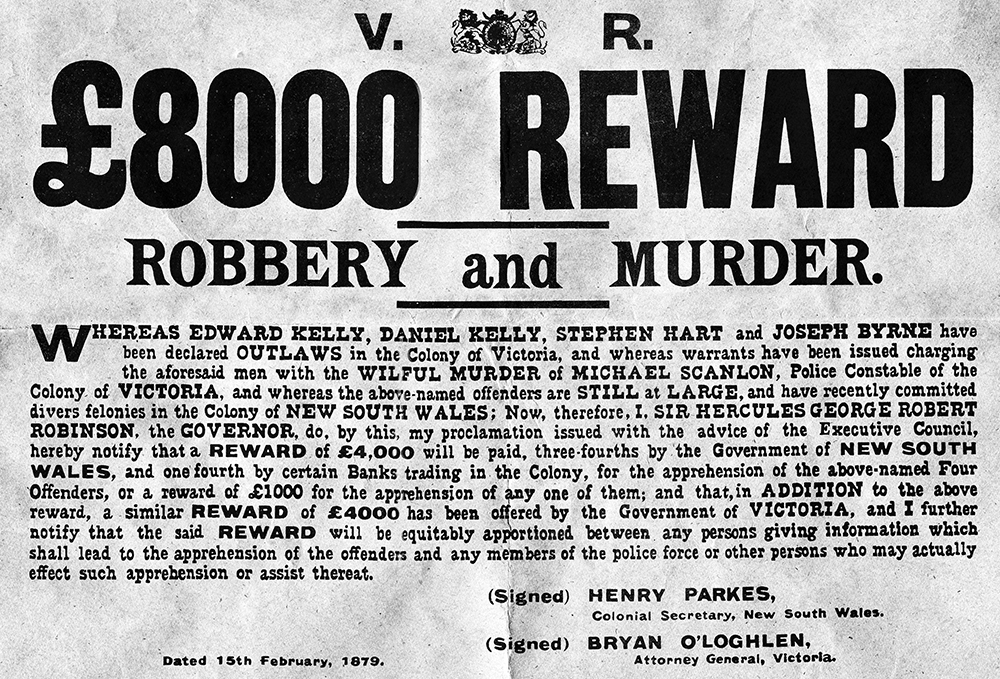

The Kelly Gang Could Be Shot On Sight

Ned Kelly, Joe Byrne, Dan Kelly, and Steve Hart were the first and only people to be declared outlaws by the Victorian Government. The Felons’ Apprehension Act 1878 meant the Gang could be shot on sight at any time – as they were legally considered guilty without the usual pre-requisite of a trial. It is interesting to note this type of Act had already been discontinued in Great Britain for a number of centuries.

Ned said this in his 1879 ‘Jerilderie Letter’

Ned had drawn up his own vision of a republic

While part of Ned Kelly’s grand plan was to derail the police train at Glenrowan and obtain hostages to trade for his mother’s release from gaol, the major goal was to declare independence for north-east Victoria. Ned put his idea to paper in much the same manner as the Jerilderie and Cameron Letters, he dictated the words while Joe eloquently wrote them out. The ‘Declaration of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria’ outlined the Kelly Gang’s vision for the region – one free of English rule and Irish Protestant interference. One where the selector had just as much rights as the squatter. When Ned was captured by police at Glenrowan they found in his pocket a document so volatile in nature the Government suppressed its very existence. While the original has since disappeared, along with many other Kelly artefacts, a respected Melbourne journalist viewed a copy of the document in 1962 at the Public Records Office in London. That too vanished without a trace. In 1969, Ian Jones interviewed Ned’s cousin Tom Lloyd Junior’s son, Thomas Patrick, who confirmed the family had a written copy of the document along with a note book containing records of meetings were the republic was discussed. However, as the document reportedly outlined the establishment of a republic, by force of arms if necessary, its very nature spoke of high treason – which carried the death penalty. Little wonder all traces have since gone to ground.

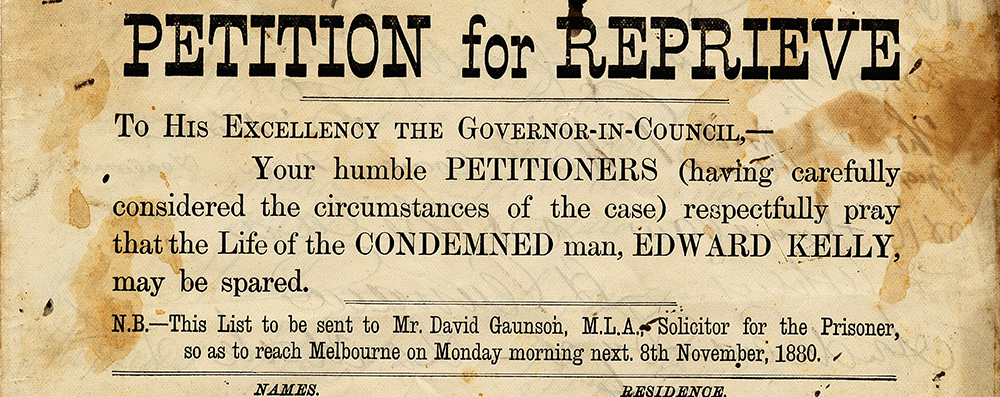

Ned’s reprieve petition attracted 32,000 signatures

After Ned Kelly was sentenced to be executed by the trail judge Sir Redmond Barry, huge public meetings were held and a petition was circulated. In less than a fortnight more than 32,000 signatures were collected for a reprieve from execution. The document, which represented over 10% of the total population of Melbourne, was then presented to the Governor of Victoria. However, the authorities ignored the pleas of clemency and belittled the owners of the signatures, labelling them vagabonds and ruffians. The execution was carried out as planned at 10am on November 11, 1880.

This is what Superintendent John Sadleir had to say about the Kelly Outbreak

To me, writing from the police point of view, the Kelly outbreak has one moral – prevention is better than cure. The whole cost of this evil business, in life and treasure, might have been avoided by a better administration of police affairs in the north-eastern district. I have shown how effective were the efforts of a few specially zealous and competent police in other places. The true Kelly country, however, was neglected; police stations were broken up, or else constables quite unequal to the task of keeping evil-doers in check, were placed in charge.

Sadleir was referring to Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick whose flagrant dishonesty and lack of morals was the primary catalyst of the Kelly rebellion.

The son of the Old Melbourne Gaol’s Governor played Ned in a number of movies

After the release of the world’s first full length movie featuring Ned Kelly in 1906, several more films focusing on the Kelly story were produced. In three of them, Ned was played by actor Godfrey Cass — real name Godfrey Castieau, who was the son of the Melbourne Gaol Governor John Buckley Castieau. As a thirteen-year-old, Godfrey had met Ned while the bushranger awaited execution in his father’s Gaol. When the Governor introduced Godfrey to his famous inmate, Ned was reported to have said, ‘Son, I hope you grow up to be as fine a man as your father.’ Godfrey played Ned Kelly for the last time in 1923, when he was aged fifty-seven.

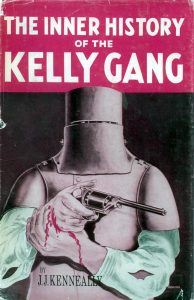

The first biography on Ned Kelly was written in 1929

Japan’s Second World War Oath of Obedience was signed by Ned Kelly

During the Second World War the Japanese tried to force POWs to sign oaths promising that they would be obedient and not try to escape. Under military law it was illegal to require undertakings of this kind. The most infamous example was the Selerang Incident in Changi when 14,609 British and Australian soldiers unanimously agreed not to sign a ‘no escape’ declaration. They were confined to the barrack square with reduced water rations. In increasingly distressing conditions, and following the deaths of several captives, the prisoners only signed after acceding to the compromise that they were signing on Japanese orders, under stress, and not voluntarily. When signing many of the Allied troops used false names – ‘Ned Kelly’ featured prominently for the Australians.

Ned is spoken about in stories of Aboriginal Dreamtime

Murder is in the eye of the beholder

On February 20, 1879, just prior to Sub-inspector Stanhope O’Connor and his native troopers joining the hunt for the Kelly Gang in Victoria, they were responsible for the murder of twenty-eight Aboriginal men shot and drowned at Cape Bedford in Far North Queensland. Known as the Cape Bedford Massacre, Cooktown based Native Police Sub-inspector Stanhope O’Connor with his troopers, Barney, Jack, Corporal Hero, Johnny, and Jimmy hunted down and subsequently ‘hemmed in’ a group of Guugu-Yimidhirr Aborigines in ‘a narrow gorge’ north of Cooktown. O’Connor proudly reported, ‘There were twenty-eight men and thirteen gins thus enclosed, of whom none of the former escaped. Twenty-four were shot down on the beach, and four swam out to the sea.’ Those four were never to be seen again. Maybe O’Connor just like bloodshed. During the Glenrowan siege he was told by one of the escaped prisoners, possibly Mrs Ryan, that there were still many people, including woman and children, held hostage at the Inn. While he thanked her for the information he did not pass it on. Instead O’Connor directed his men to increase their rate of fire. A fine gentleman indeed.

They’re still talking about Ned Kelly

Each week, on average, there is a newspaper story published somewhere in the world with Ned Kelly as the topic. Ned has nearly eleven million pieces of information available online through Google search. He has been commemorated through music, words, paintings, and film. More books, songs, and websites have been written about the Kelly Gang than any other group of Australian historical figures. And when you add the wide variety of Kellyana to the amalgam – such as clothing, toys, alcohol, tattoos, etc. – then Ned Kelly truly is Australia’s greatest folk hero.