The McCormick Incident

Captain Jack Hoyle (retired)

He also had an argument with another bloke and because of this he knew that the man and his wife were trying to have children, unsuccessfully. So what he did was send a pair of calf testicles to the wife, with a note saying ‘These will be more use to you’. This shows what a nice type of man he was. The type you’d bring home to meet your sister. Pig’s patootie you would.

Edgar Penzig ABC ‘Collectors’ 22 May 2009

The Kelly critics use this incident as a useful character reference for Ned Kelly. In an article published in the Murdoch press in May 2006 entitled ‘Legend masks the terrorist’ Christopher Bantick writes: ‘…he sent a pair of calf’s testicles to a neighbour’s wife suggesting that she should give these to her husband. If there had been aerosol paint cans in 1878, Ned’s tag would be all over Victoria’s north east. Kelly was a colonial thug.’

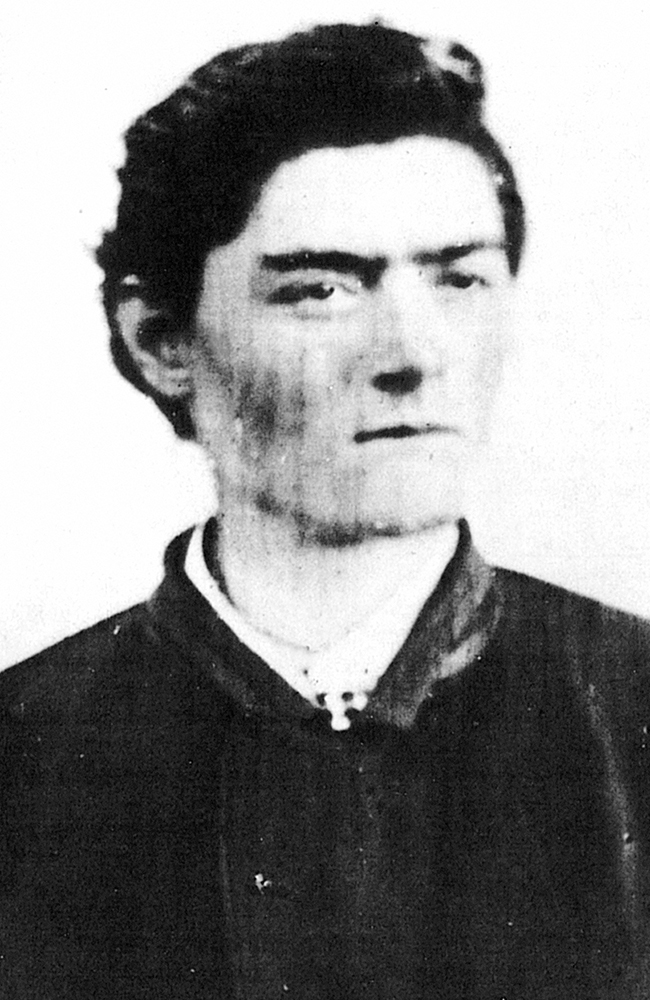

The Australian Police Journal in December 2006 states concisely: ‘His first stint in prison began in 1870 with a six month sentence for a vicious assault and obscene language.’

Superintendent Nicholson, then in charge of the North Eastern district warned: ‘Young Kelly was a terror to the locality and persons were afraid to prosecute.’

But not Jeremiah McCormack, sometimes called McCormick, and his formidable wife. Reading the above quotes from assorted experts paints a nasty picture of the teenage Kelly. But is this the full story? (Note: Because of the confusion with the hawker’s name, any quotes used will feature each author’s spelling).

In the Cameron Letter Ned Kelly writes: ‘I was once accused of taking a hawker by the name of McCormack’s horse to pull another hawker named Ben Gould out of a bog.’

He does not elaborate, but in the Jerilderie Letter it is the opening subject and he waxes lyrical on the events of Sunday the 30th October 1870: ‘the ground was very soft a hawker named Mr. Gould got his wagon bogged between Greta and my mother’s house on the eleven mile creek, the ground was that rotten it would bog a duck in places so Mr. Gould had to abandon his wagon for fear of loosing his horses in the spewy ground.’

He does not elaborate, but in the Jerilderie Letter it is the opening subject and he waxes lyrical on the events of Sunday the 30th October 1870: ‘the ground was very soft a hawker named Mr. Gould got his wagon bogged between Greta and my mother’s house on the eleven mile creek, the ground was that rotten it would bog a duck in places so Mr. Gould had to abandon his wagon for fear of loosing his horses in the spewy ground.’

Kelly then tells the tale of a horse: ‘Mr. John had a horse called Ruita Cruta, although a gelding was as clever as Old Wombat or a stallion at running horses away and taking them on his beat. . .he enticed McCormack’s horse’

According to the letter: ‘Ben Gould saw McCormack’s horse and ‘sent his boy (Jim Kelly) to take him back to Greta. When McCormack’s got the horse they came straight to Goold (sic) and accused him of working the horse; this was false and Goold was amazed at the idea I could not help laughing to hear Mrs. McCormack accusing him of using the horse after him being so kind as to send his boy to take him from the Ruta Cruta) and take him back to them.’

Ian Jones in A Short Life describes the situation as ‘a silly squabble between some hawkers’ and writes: ‘When Ned said dryly to Gould, “That’s for your good nature!’ Mrs. McCormack flew at him, accusing him of taking the horse from Greta to try to pull Gould’s wagon out of the bog. Ned commented, ‘I did not say much as my mother was present’.

For 15 years old Ned Kelly such an accusation meant trouble. He had escaped a prison sentence in May of 1870 but was thought to have betrayed Harry Power and was viewed as a ‘black snake’ by some members of the clan. Life for the now ‘Notorious’ Ned Kelly or “Power’s mate” was complicated by this inference, which was thought to be popularized by his uncles Jack Lloyd and Jimmy Quinn. Kelly wrote of his problems on the 28th of July to Sgt Babington, the policeman who had shown him kindness during his time in police custody in Kyneton.

For 15 years old Ned Kelly such an accusation meant trouble. He had escaped a prison sentence in May of 1870 but was thought to have betrayed Harry Power and was viewed as a ‘black snake’ by some members of the clan. Life for the now ‘Notorious’ Ned Kelly or “Power’s mate” was complicated by this inference, which was thought to be popularized by his uncles Jack Lloyd and Jimmy Quinn. Kelly wrote of his problems on the 28th of July to Sgt Babington, the policeman who had shown him kindness during his time in police custody in Kyneton.

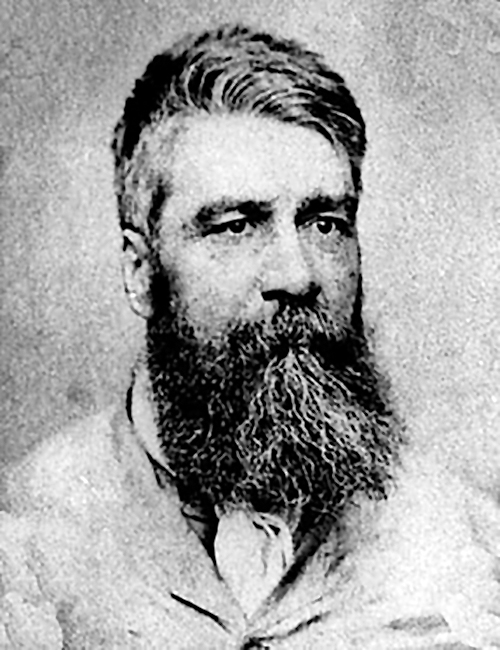

When nothing came of his plea he seems to have turned to another policeman, Senior Constable Edward Hall, a huge 16 stone man who Ian Jones describes as having ‘shown a propensity for violence, extraordinary vindictiveness, and a readiness to lie. He would display the same traits in his latest posting.’ Hall showed the confused Kelly a facsimile of the kindness of Sgt Babington and by the 26th of August, Hall had asked of Ned ‘I wish you would get up a row’ And get up a row he did with Uncle Jimmy Quinn, Jimmy’s confusing no relation brother-in-law Pat Quinn and a man called Kenny.

Starting with Ned deliberately riding his horse into Uncle Jimmy as he and his two drinking companions stood outside O’Brien’s Hotel Greta, it ended with Hall’s head cracked open with a stirrup iron wielded by the enraged Pat ‘the Dubliner’ who received three years imprisonment and Uncle Jimmy three months. When Kenny came before the court, Kelly earned the enmity of Hall by telling the court:’ Constable Hall came with me to Wangaratta and advised me to swear an information against Kenny . . . Wish to withdraw the charge. Would not have sworn an information against the defendant if not for Constable Hall.’

Kenny was discharged and Hall stated ‘Kelly is not a particular friend of mine.’ With the clash of the hawkers, Hall would have his revenge. What might have been a simple misunderstanding between rivals became the means of settling scores, and earning Hall some approval from his superiors for ‘taking the flashness’ out of the young Kelly. It would also earn him a much needed two pound reward. What happened next would only make matters worse, but only for the ‘notorious’ Ned.

Kelly writes: ‘that same day me and my uncle was cutting calves Gould wrapped up a note and gave them to me to give them to Mrs. McCormack.’ The note was even more specific, obscene and instructional than Edgar Penzig states, a tasteless show of contempt thought up by Gould. Ian Jones states: ‘Ned hesitated to become involved. He gave the package to his cousin, young Tom Lloyd, for delivery to (Mrs.) McCormick.’ Unfortunately Tom, seeing Mr. McCormick, handed him the package with a cheery ‘Ned Kelly gave me this parcel for you.’ Jeremiah did not find the insulting suggestion a cause for mirth and confronted Ned a few days after as he rode past their camp at Greta.

Ned continues the story: ‘McCormack said he would summons me I told him neither me or Gould used their horse. He said I was a liar & he could welt me or any of my breed I was about 14 years of age (sic) but accepted the challenge and dismounting when Mrs. McCormack struck my horse in the flank with a bullock’s skin it jumped forward and my fist came in collision with McCormack’s nose and caused him to loose his equilibrium and fall prostrate I tied up my horse to finish the battle but McCormack got up and ran to the police depot.’

Ned’s deadpan joke makes light of the serious consequences of this farce. Charles Osborne writes in his 1970 book ‘Ned Kelly’: ‘Although the charge was a relatively trivial one, the police had evidence enough to convict him.’ The strong denial of Gould’s use of the McCormicks’ horse is challenged by JJ Kenneally’s ‘The Inner History of the Kelly Gang’ in which Tom Lloyd ‘The Providor’ and the boy who delivered the parcel, was the main source of information. JJ happily writes:

McCormack’s horse got away from the camp and was making its way home to Benalla. Ned Kelly recognized the horse and caught it with the intention of returning it to its owner. Someone suggested that now, with an extra horse-power, Ben could be pulled out of the bog. This was done. McCormack not only did not thank him for his neighbourly act, but he accused him of stealing the horse to pull his rival out. Ned replied: “Your horse was making its way back to Benalla, but” continued Ned “I did pull Ben Gould out of the bog, and brought him back to you”.

McCormick claimed that Kelly rode up to him swearing and exclaiming “I will ride my horse over you and kill the bloody lot of you, you bloody wretches.” When Hall was brought to the scene, Ned helpfully explained to the Senior Constable “I told him they accused me of using their horse and I hit him and I would do the same to him if he challenged me.” John Molony in his 1980 I am Ned Kelly writes:

Ned’s involvement was peripheral to that of Gould, but it was Ned whom Senior Constable Hall, mindful as ever of the desirability of keeping the peace in Greta, hauled in to Wangaratta charged with assault on the person of Jeremiah McCormick and insulting behavior to his wife Margaret. The lad was fifteen, but represented before the court as being nineteen and as following the vocation of a ‘tramp’, although in respect of his place of origin it was recognized that he was a ‘native’.

Max Brown in Australian Son describes the trial: ‘McCormack told Wangaratta court that Kelly had threatened to shoot him and he’d been forced to sit up till midnight with a loaded pistol. As a result Ned was sentenced to three months gaol for offensive behavior and fined ten pounds, in default three months gaol, for assault. Since he was unable to pay the fine this meant six months in Beechworth. In addition he was bound over to keep the peace.’

The author also notes ‘While Ned served his first term in gaol, horse stealing went on unabated’ Ben Gould had testified that it was he who had written the note, Jack Lloyd testified that Mrs. McCormick had thrown a stick at Kelly’s horse but added that Ned had knocked McCormick over with his horse. Hall claimed that Ned had confessed to him in the lockup that he wrote the note. Breaking rocks in the hot sun, Ned fought the law and the law won.

Charles Osborne writes: ‘there can be no doubt that his six month sentence had a distinctly hardening effect on the already unruly youth.’ adding ‘McCormick himself, having laid the charge against Ned, then tried to withdraw it. But the police refused to allow the charge to be withdrawn; this was their first real chance to put young Kelly behind bars, and they were not willing to pass it up.’ And Hall, in his report of the 17th of November confirms this in his report on ‘young Kelly’ as he called him.

Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick is always the villainous policeman in the Kelly story, but examination of the actions of Senior Constable Edward Hall show him to be the man that changed the life of Ned Kelly forever. It is interesting to note that Greta police station in the 1870’s was manned by a number of men who had been transferred from another district for misconduct. Hall and Flood had both been in trouble with their superiors for transgressions and were keen to make amends, improve their rank and collect the monetary rewards on offer. Fitzpatrick was also looking for a way to rehabilitate himself with his superiors and Ned Kelly was the one fifteen year old in Victoria that the Police Commissioner Standish and Superintendents Nicholson and Hare wanted to see behind bars. Since Ned’s brush with the upper echelon of the law and his near gaol experience at Kyneton ‘Power’s mate’ was forever ‘notorious’.

Senior Constable Edward Hall’s report is an unusual document, unlike most police reports, Hall writes as if a novelist, with the hero of his story one S. C. Edward Hall.

‘A man named McCormick, a hawker, complained to the Senior Constable that young Kelly had assaulted him by riding his horse against him and thereby knocking him down and that he had also sent a paper containing the testicles of a Bull to his Wife and a letter in which there was language of the most disgusting kind he thinks is not necessary to repeat here.’

‘A man named McCormick, a hawker, complained to the Senior Constable that young Kelly had assaulted him by riding his horse against him and thereby knocking him down and that he had also sent a paper containing the testicles of a Bull to his Wife and a letter in which there was language of the most disgusting kind he thinks is not necessary to repeat here.’

Hall then confirms McCormick was reluctant to press charges: ‘McCormick further stated that he was afraid to take proceeding against Kelly, under these circumstances the Senior Constable went to Wangaratta with McCormick and got him to swear an information against Kelly stating that he was in grievous bodily fear of his life. On the strength of the information he got a warrant for his arrest and when he was in custody he charged him with the offences entered in the margin of this report.’ No, Hall did not charge himself, ‘he’ and ‘his’ refer to two different people! It is interesting to note that Kelly’s testimony at his uncles’ trial for assaulting Hall echoes the same insistence on the part of the eager Senior Constable that the charges must be laid.

Hall had originally charged Kelly with three offences: ‘did violently assault one Jeremiah McCormick’. ‘Insulting behaviour in a Public Place to Margaret McCormick’ and ‘did use most indecent and obscene language to Margaret McCormick.’ Hall reports ruefully ‘at the suggestion of the court, the Senior Constable withdrew the third charge’ but states with pride, ‘the conviction of this man will save the police a good deal of trouble during the summer months.’ He then claims that from ‘information received’ Ned was planning to take up arms and ‘go bush’ with Allen Lowry alias Davis alias Cook. Police Chief Commissioner Standish approved the reward on the back of the report.

The hand of fate and the supernatural are always close by in the Kelly story, adding a mythic quality to the true story. When Ned entered Beechworth Gaol to begin his sentence, the day after his trial, the date was the 11th of November 1870. Ten years to the day of his execution. While Kelly’s family waited for his release from his first prison term, Senior Constable Hall was also waiting.

Tasmanian superintendents of convicts Jeremiah McCormick was a former superintendent of convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and Justin Corfield in the ‘Ned Kelly Encyclopedia ‘refers to his wife as a ‘convict girl’ Corfield also states her Christian name was Catherine, not Margaret as reported by Hall (‘but everyone knew her as Nancy’ – bad Beatles joke). He also states their marriage may have been ‘bigamous’.

Ned describes in the Jerilderie letter Mrs. McCormick giving ‘good substantial evidence as she is well acquainted with that place called Tasmania better known as the Dervon or Vandiemans land. And McCormack being a Policeman over the convicts and women being scarce released her from that land of tyranny, and they came to Victoria and are at present residents of Greta’.

The significance of the McCormack’s challenge to Kelly seems to be lost on most authors. ‘He said I was a liar & could welt me or any of my breed’ states Ned and would have been interpreted as a slight on his father, the ‘old lag’ from ‘that land of bondage and tyranny’. Ian Jones points out that Ben Gould ‘had also been a convict in Tasmania’ and that McCormick was a ‘convict constable’, a ‘turncoat who joined the ‘field police’ and fiery little Ben Gould would have carried this hostility into his free life’. The McCormicks had been living at Avenel and may have had knowledge or dealings with the Kellys before their move to Greta. Even Kelly critic Alex McDermott writes in his annotated ‘The Jerilderie Letter’ ‘Ned’s innocence or guilt in this incident is difficult to establish. The McCormacks were recent arrivals in the area and Gould had fiercely contested their presence in his ‘patch’.

As Ned states the McCormicks were still residents of Greta in 1879, and Mrs. McCormick was an eager informant to the police. On the 16th of October 1879 an unnamed policeman reported that ‘Mrs. Mc states that she is satisfied the outlaws are in Skehan’s paddock one mile + half above Oxley and on the King River. And their horses are there also, although they may be shifted occasionally to the paddock of a one eyed man named Dwyer. That she has seen pudding and other food recently taken by the sons of Widow McCauliffe who lives near Alex Smith on Old Melbourne Road via Greta. She has seen Kennedy’s watch with Dennis McCauliffe and also Scanlon’s ring.’

As Ned states the McCormicks were still residents of Greta in 1879, and Mrs. McCormick was an eager informant to the police. On the 16th of October 1879 an unnamed policeman reported that ‘Mrs. Mc states that she is satisfied the outlaws are in Skehan’s paddock one mile + half above Oxley and on the King River. And their horses are there also, although they may be shifted occasionally to the paddock of a one eyed man named Dwyer. That she has seen pudding and other food recently taken by the sons of Widow McCauliffe who lives near Alex Smith on Old Melbourne Road via Greta. She has seen Kennedy’s watch with Dennis McCauliffe and also Scanlon’s ring.’

Sergeant Whelan of Benalla wrote a memorandum ‘for the superintendent’s information’ Whelan told Sadlier: ‘Of a statement made to me this day ( the 16th) by Mrs. McCormick a Hawker’s wife who has resided at Greta for many years and has just come yesterday from the King River. There is a fifth man with them . . . They have a sentry on watch day and night.’

So the boys did not miss out on their pudding but the Greta Mob were being watched and reported on by the vengeful Mrs. McCormack. She had not forgotten her parcel.

Far from painting a picture of a nasty Ned as oft stated by his critics, the McCormick incident does not indicate a central role for Ned Kelly in the sending of the testicle epistle. Kelly’s youth led him to be caught in a grubby affair that ignored the main protagonists and the trifling nature of the incident and turned it into an excuse to put Kelly behind bars on one of Superintendent Nicholson’s ‘however paltry’ charges. Hall had done well with his gaoling of two Quinns and a Kelly and the McCormick’s had their satisfaction. Ben Gould escaped any criminal liability and became an active Kelly sympathizer, Jack Lloyd escaped scrutiny and Ned enjoyed his first term at ‘college’.

An interesting exercise would be to look at all the things Ned Kelly did NOT do in the years of his outlawry. Rather than use this as an excuse for revenge, Kelly avoided such confrontations. There were no raids on the stately homes of squatters, no vengeance against the likes of the McCormicks. His enemies were no longer those who had personally crossed him. After the gaoling of the sympathizers and the denying of selection to local farmers, Kelly fought against the institutions that in Kelly’s eyes oppressed all.

References

Christopher Bantick ‘Legend Masks the Terrorist’ Courier Mail Wednesday May 17, 2006.

Martin Leonard ‘The Murderer Unmasked’ Australian Police Journal December 2006.

Ian Jones Ned Kelly – A Short Life 3rd Edition 2008 Published by Hachette Australia.

Charles Osborne Ned Kelly 1970 Published by Anthony Blond Limited.

J.J. Kenneally The Inner History of the Kelly Gang 8th Edition 1969 Published by The Kelly Gang Publishing Company.

John Moloney I am Ned Kelly 1980 Published by Allen Lane.

Justin Corfield The Ned Kelly Encyclopedia 2003 Published by Thomas C. Lothian Pty Ltd.

Alex McDermott The Jerilderie Letter 2001 Published by The Text Publishing Company.

Public Records Office of Victoria The Kelly Historical Papers.

Author’s Note: In 1971 US pop group Three Dog Night, whose extensive knowledge of Australian culture is reflected in the group’s name, claimed that ‘Jeremiah was a bullfrog’.