When Sergeant Steele jammed his revolver in Ned Kelly’s face after capture, Constable Bracken told him: ‘You shoot him and I’ll shoot you. Take him alive.’ Steele then kicked the wounded Kelly in the groin, provoking Ned to a last surge of resistance. Little wonder the 1881 Royal Commission into the Victorian Police Force’s handling of the Kelly outbreak found some members either inept, contemptuous or downright corruptible. Just pause for a moment at the Stringybark Creek shootings. With Kennedy fighting for his life against four desperate men, how could a fellow officer like McIntyre simply grab the nearest horse and flee? So much for mateship…

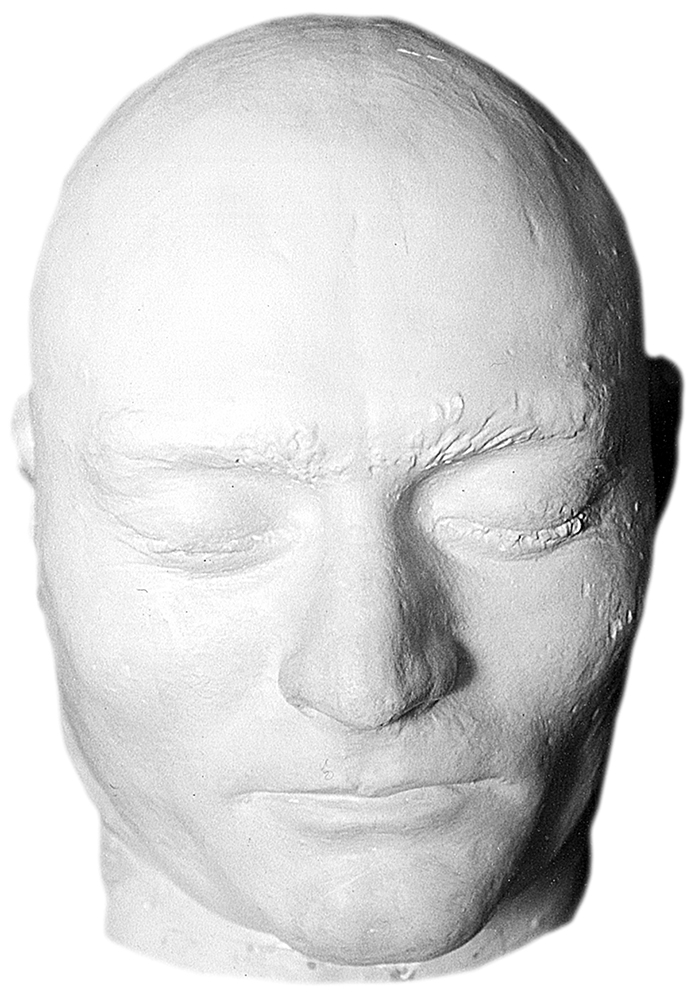

Ned Kelly’s death mask was completed immediately after the execution by Maximilian Kreitmayer, proprietor of Bourke Street Waxworks. After his execution, Kelly’s hair and beard were shaved, his head was cut off, and his brain was removed. Medical students then dissected the body. The flesh was boiled away from the skull, then shaved and oiled to become a ghoulish souvenir – a clerk’s paperweight. While the headless body was originally buried in unconsecrated ground next to the Gaol, and eventually reburied in Greta Cemetery, the skull’s whereabouts are still unknown.

Ned Kelly’s death mask was completed immediately after the execution by Maximilian Kreitmayer, proprietor of Bourke Street Waxworks. After his execution, Kelly’s hair and beard were shaved, his head was cut off, and his brain was removed. Medical students then dissected the body. The flesh was boiled away from the skull, then shaved and oiled to become a ghoulish souvenir – a clerk’s paperweight. While the headless body was originally buried in unconsecrated ground next to the Gaol, and eventually reburied in Greta Cemetery, the skull’s whereabouts are still unknown.

Before the Kelly Outbreak and well into the 1881 Royal Commission, the police force, particularly the senior management, was constantly questioned. Little wonder when you discover the Victorian Chief Commissioner of Police, Captain Standish, emigrated to Australia from England under a false name in a bid to escape massive gambling debts. Even in his ‘new life,’ he continued to gamble heavily, once losing the equivalent of six months’ salary in one night.

I don’t know how many police there were but I think there must have been fully 150 and all the fellows firing on that house at once. I can tell you it was something awful. The room I was in was fairly riddled with balls coming in every direction breaking the clock and other things on the mantlepiece and coming through the windows and hitting the table and sofa. That will tell you how close they were to us and the worst of it was they knew that we were in there. It was all nonsense of them saying that they would have let us out if we had tried to get out, see when Mick Reardon tried to get out how he was shot and the same with Martin Cherry, it was Sergeant Steele that shot Martin and Mick Reardon too.

T. H. Cameron (who was sixteen years old when taken hostage at the Glenrowan Inn)

A harsh English judicial system coupled with a corrupt police force favouring the aristocratic squatter presented a monstrous burden for the average selector on the land. Many were singled out for questionable conduct by the Victorian Police Force, who locked up selectors for ‘knowing’ Ned Kelly. Men were held for months on end while their crops withered and their stock was seized or stolen. Others were simply denied land selection, which furthered their misery. And all the while, the squatters grew fat on their spoils. Towns and monuments are named after these same men. Then again, we build statues of murderers like John Batman*, but hey, he ‘only’ killed Aboriginals. To say Ned Kelly bought this all on himself is laughable and naive. Not convinced? Then check out the biographies of infamous characters who walked the colonial stage during the Kelly outbreak.

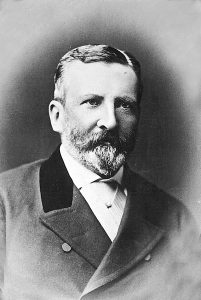

Captain Frederick Charles Standish

Captain Frederick Charles Standish was in charge of the Victorian police during the hunt for the Kelly Gang. In 1852 he sold his mortgaged properties to pay gaming debts then fled England for Australia. By 1858 he was appointed Chief Commissioner of Police in Victoria. Interestingly, he had been rejected for the same appointment five years earlier, when he applied under an assumed name.

However, even in his new life he continued to gamble heavily, once losing the equivalent of six months salary in one night. Standish did not believe in any formal training for police. He also believed cracking down on sly-grog was ‘inoperable’ even while he actively prosecuted shanties like Ellen Kelly’s.

However, even in his new life he continued to gamble heavily, once losing the equivalent of six months salary in one night. Standish did not believe in any formal training for police. He also believed cracking down on sly-grog was ‘inoperable’ even while he actively prosecuted shanties like Ellen Kelly’s.

Captain Frederick Charles Standish, short service officer in the Royal Artillery, was a younger son of an English county family, who – there being no move in Britain to open up the estates to the land-hungry – had gravitated to Melbourne. Of liberal upbringing, although born Roman Catholic, and with broader views and greater sensibility than most, he was a pleasant companion and man of educated taste who found other things in life than hard work. As a leading Mason and member of the Melbourne Club, where in fact he lived, he was on cordial terms with society figures who had set his predecessor aside to make way for an officer and a gentleman.

For the well-to-do establishments, Standish favoured an unofficial licensing system. These premises not only operated with impunity but expanded into prostitution and gambling. He believed gambling was the domain of detectives, not beat police, so rogues setting up gaming tables at racecourses knew they had to pay detectives a fee. Standish also held personal interests in a number of Melbourne’s brothels.

He resigned as Commissioner in 1880 and soon after was nearly thrown through a window of the Melbourne Club after he referred to a guest in a ‘provocative name.’ Standish died from cirrhosis of the liver less than three years after Ned’s execution.

Senior Constable Edward Hall

When Isaiah Wild Wright called into the Kelly homestead in early April 1871 he unwittingly set in motion one of the more violent events in the life of the young Ned Kelly. Wild told Ned, whom he had never met before, that he had lost his horse in the nearby scrub and asked if he could borrow one of his. In return, if Ned found his horse he could ride it until he called back. Ned later described the horse ‘as a remarkable chestnut mare, white faced, docked tail… branded (M) as plains as the hands of a town hall clock’.

At sixteen, Ned received a brutal pistol whipping from Constable Edward Hall who then proceeded to commit perjury to gain Kelly’s conviction.

At sixteen, Ned received a brutal pistol whipping from Constable Edward Hall who then proceeded to commit perjury to gain Kelly’s conviction.

Ned found the horse on the way to Wangaratta and took it with him. During his stay he even allowed the daughters of the publican to ride the mare. What Ned didn’t realise and what Wild had forgot to tell him was that the animal was stolen. As Ned was approaching home he was stopped by Senior Constable Hall on the Greta bridge. Hall told the sixteen-year-old Kelly that he had some papers that needed signing at the police camp. Ned followed Hall but refused to dismount and enter the building.

Hall then declared that Ned was under arrest for horse stealing, and made a grab for the young man. The fight that ensued was both bloody and violent. Hall weighed over one hundred and two kilograms (sixteen stone), Ned was a boy of sixteen. Yet Kelly managed to over power the raging Constable even though Hall had fired his service revolver at Ned three times (all three shots had misfired). According to Ned:

Instead of me putting my foot on Hall’s neck, and taking his revolver and putting him in the lock-up, I tried to catch the mare. I kept throwing him in the dust until I got him across the street the very spot where Mrs O’Brien’s Hotel stands now the celler was just dug then there was some brush fencing where the post and rail was taking down and on this I threw big cowardly Hall on his belly I straddled him and rooted both spurs into his thighs he roared like a big calf attacked by dogs and shifted several yards of fence I got his hands at the back of his neck and tried to make him let go of the revolver but he stuck to it like grim death to a dead volunteer he called for assistance to a man named Cohen and Barnett, Lewis, Thompson, Jewitt and two blacksmiths who was looking on. I dare not strike any of them as I was bound to keep the peace or I could have spread those curs like dung in a paddock they got ropes and tied my hands and feet and Hall beat me over the head with his six chambered Colts revolver.

Hall hammered Ned over the head with his pistol half a dozen times. The wounds were so severe that an urgent dispatch was sent to Wangaratta for a doctor and two troopers. The doctor administered nine stitches then the following day Ned was carted off to the Wangaratta lock-up. After three months on remand, Ned was convicted of receiving a stolen horse. Yet, while Wild received eighteen months for actually stealing the mare, Ned received three years with hard labour.

Unfortunately for Ned, Senior Constable Hall was under explicit instructions to “get” him as soon as possible after his release from Beechworth. Hall recognised the mare from the Police Gazette and tried to arrest him when he rode into Greta. An extremely big man, Hall nevertheless must have been nervous of the teenager, for, in his official report, he admitted he failed to unseat Kelly and tried to shoot him.

Max Brown Australian Son

During the trial it was noted that Hall had pistol whipped and tried to shoot an unarmed youth. However, instead of censure Hall received a reward. This was the same man who had previously been charged with assault and perjury at Eldorado, forced out and transferred to Broadford only to leave there in similar disgrace for ‘violent and vindictive behaviour’. Afterwards Hall feared reprisals from the Kelly clan and refused lone mounted patrols. The massively overweight Constable continued to pile on the kilograms, which resulted in the inability of government horses to bear his weight. Later the same year Hall was dismounted and transferred out of the district.

Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick

In the late afternoon of Monday, April 15, 1878, Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick visited the Kelly homestead at Greta. The next morning, he rode into Benalla with a lacerated wrist. Whatever the circumstances surrounding his wound, this incident, above all others, was the catalyst for the Kelly outbreak. Fitzpatrick was a lazy, weak-willed man who, against orders, had gone to the Kelly homestead alone to arrest Dan Kelly.

Constable Alex Fitzpatrick, on record as ‘a liar and a larrikin’, tried to rescue his police career by the arrest of Dan Kelly at the Kelly home on 15 April 1878. A pass at Kate Kelly triggered the fateful brawl. Image: Victoria Police Historical Unit

Constable Alex Fitzpatrick, on record as ‘a liar and a larrikin’, tried to rescue his police career by the arrest of Dan Kelly at the Kelly home on 15 April 1878. A pass at Kate Kelly triggered the fateful brawl. Image: Victoria Police Historical Unit

At Beechworth on October 9 1878, before the trial judge Sir Redmond Barry, the charge of ‘aiding and abetting Ned Kelly with shooting with intent to murder Constable Fitzpatrick’ was levelled at the three defendants Ellen Kelly, William Skillion and William Williamson. Fitzpatrick was the only witness for the prosecution, and despite numerous witnesses countering his claims, all three were found guilty and sentenced to hard labour. After Stringybark Creek, Fitzpatrick was transferred to Lancefield.

He was there only nine months before his superior, Senior Constable Mayes, accused him of ‘not being fit to be in the police force; that he associated with the lowest persons in Lancefield; that he could not be trusted out of sight; and that he never did his duty.’ Needless to say, these charges led to Fitzpatrick’s dismissal from the police force, but by this stage, it was too late for Ned Kelly and his clan. The 1881 Police Royal Commission heard evidence from Fitzpatrick that during his three years in the police force, he had pleaded guilty to numerous other charges of neglect of duty and misconduct.

Fitzpatrick described finally how he came to and found he had a ball in his wrist, and how Ned insisted on prising it out with a penknife despite his preference for seeking treatment in Benalla. After agreeing to say nothing about the matter, he left the house about 11 pm. Ned poured ridicule on Fitzpatrick’s story. The trouble began, he said, when Fitzpatrick produced a telegram instead of a warrant and Mrs Kelly ordered him off the premises. The trooper had drawn his revolver, which prompted her to say, “It’s just as well Ned is not home or he would ram that down your throat!” This had given Dan the cue to cry, “Ned is coming now!” He had clapped a wrestling hold on Fitzpatrick.

Max Brown Australian Son

After the Royal Commission, William Williamson was pardoned, suggesting that the court was wrong about one important fact. Evidence does show Ned was present at the homestead on that fateful day, but as the doctor who tended Fitzpatrick’s wounds stated in court, ‘of the two wounds present, one definitely could not have been made by a bullet, and both were only skin wounds yet the constable had the smell of brandy on him.’ The question still remains today: did the Kelly outbreak arise due to one constable’s battle with the bottle and his countless lies and half-truths?

Sergeant Arthur Steele

Sergeant Arthur Steele, who from 1877 was in charge of the police at Wangaratta, is nowadays remembered more for his murderous rampage during the siege of Glenrowan than any other event in his unimportant life. Steele arrived at Glenrowan around 5.30am during the morning of the siege. Reports stated that he was dressed in a tweedy sportsman’s outfit and ‘desperate to kill something’.

I have just shot Mrs Jones in the tits!

I have just shot Mrs Jones in the tits!

Sergeant Arthur Steele

Glenrowan

When Mrs Reardon and her four children — a babe in arms, her seventeen-year-old son and two young daughters — attempted to flee during an apparent cease-fire, Sergeant Steele had the family firmly lined up in the sights of his shotgun. Firing as they ran across the open spaces towards the railway station, he wounded both Mrs Reardon’s baby and her son. Her son was forced to retreat back to the Inn with one of his sisters.

Events were now to occur which threw a curious light on police concern for civilians, and in particular, on the enthusiastic Steele. With the arrival of new police, it must have been obvious to the prisoners that the fire would increase so they decided on a fresh attempt to leave. Mrs Reardon, wife of one of the fettlers with a large family, spoke to the outlaws in the passage. “Yes, you can go, but the police will shoot you,” said one. “They will take you for one of us.”

Max Brown Australian Son

Steele’s barrage continued until Constable Arthur yelled, ‘If you fire at that woman again, I’m damned if I don’t shoot you!’ However, after the siege, instead of being charged with attempted murder, Steele receives a sizeable portion of the reward money – over two hundred and ninety pounds for his part in the capture. The 1881 Royal Commission recommended that Steele be reduced in ranks because of his ‘highly censurable’ failure to follow the Kelly Gang when he led a heavily armed party in the Warby Ranges near Wangaratta in November 1878. However, this was not implemented. It is curious to note that the Royal Commission made no mention of Steele’s murderous behaviour at Glenrowan. Steele’s own death eventually occurred at Wangaratta in 1914.

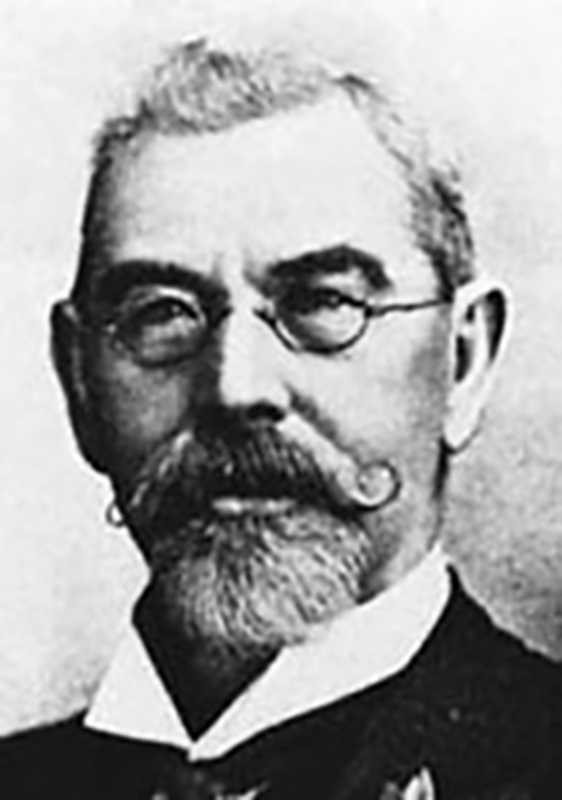

Detective Michael Ward

From an early age both Joe Byrne and Aaron Sherritt became prime targets for Ward. It would be Ward’s shrewd and often illegal activities which set in motion the killing of Sherritt. His manipulative manner fitted well with his police agenda. Ward was the man responsible for setting up the unsuccessful spy ring in a vain attempt to catch the Gang. When it became apparent his network was a failure, Ward put in motion a blood thirsty trap using Sherritt as the bait.

Joe and Dan rode up to a selection in the Woolshed opposite the Sugarloaf where Sherritt was working. They already knew something of Aaron’s dealings with the police, in particular of his meetings with Detective Ward whose affairs with servant girls were common gossip. Ward’s waxed moustache, which he liked to twirl, gave the lie to his many disguises.

Joe and Dan rode up to a selection in the Woolshed opposite the Sugarloaf where Sherritt was working. They already knew something of Aaron’s dealings with the police, in particular of his meetings with Detective Ward whose affairs with servant girls were common gossip. Ward’s waxed moustache, which he liked to twirl, gave the lie to his many disguises.

Max Brown Australian Son

By spreading rumours, falsifying reports, and even stealing a saddle. Ward persuaded Jack Sherritt, Aaron’s brother, to steal a saddle from Aaron’s bride and plant it in the Byrne homestead. On information provided by the Sherritt family, Joe’s brother Paddy, and Mrs Byrne would be arrested for theft. Ward, therefore managed to put Sherritt under the spot light. By making Aaron his number one informer, even if his leads were vague at best, both Joe and Ned were alerted to a spy in their midst. Joe took it upon himself to put an end to Sherritt’s double dealing. A dire warning by Joe to Aaron’s mother was ignored by Sherritt, who sealed his fate by not leaving Kelly country.

On one occasion Detective Ward threatened to shoot me if I did not tell him where my brothers were, and he pulled out his revolver. The police used to come here and pull the things about.

Grace Kelly, age fourteen

To highlight the lunacy of the Reward Board, who were charged with distributing the £8000 after the destruction of the Kelly Gang, Detective Michael Ward was handed £100 even though he was not present at the siege. Instead the money was awarded because of his ‘connection with the employment of Aaron Sherritt.’ Employment which ended in murder. Ward was as guilty as if he had pulled the trigger himself.

Detective Ward, having received one hundred pounds of the reward, was found guilty of misleading his superior officers and the Commission recommended he be censured and reduced one grade. As for the hut party, Armstrong had already left the country. As for the rest, already awarded a share of the reward, they were charged with disobedience and cowardice, and the Commission recommended their dismissal.

Max Brown Australian Son

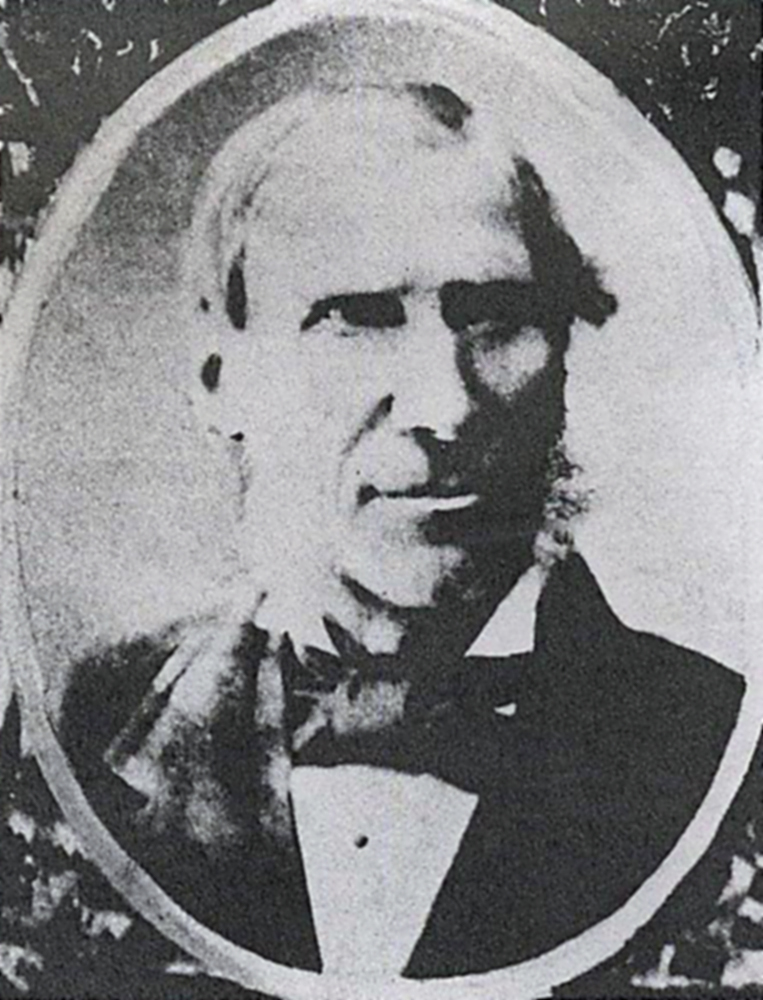

James Whitty

James Whitty was an egotistical squatter who became Ned Kelly’s nemesis. Squatters like Whitty often occupied important social positions in local communities and were prepared to use such positions to frustrate selection. They could choose the best pastures, mainly along river banks and watering holes, effectively picking the eyes out of the land or ‘peacocking’, as it was known back then.

James Whitty. Image: Burke Museum, Beechworth

James Whitty. Image: Burke Museum, Beechworth

Dummying was also a famous tactic used by squatters, who paid a man to select land. He would then transfer it back to the squatters. The squatters, with their social influence, were able to place roads through selections. They sat on the boards set up to overview the land laws effectiveness. City officials, oblivious to the ways of the country, accepted these committee findings as gospel.

All this resulted in land lock where quality pastures became unavailable to selectors. These selectors were mainly made up of diggers who had become tired of the gold chase through the bush and decided to settle on the land instead. Squatters resented the diggers calls to ‘Unlock the land’ as they saw the country as their own. They had pioneered the land during the 1830s and felt a moral right to it. Eventually the Victorian Parliament passed legislation which allowed any man or single woman the right to select parcels of land to the size of 640 acres (reduced to 320 acres in 1869). The selectors had to pay off the land and make certain improvements to it to the tune of one pound per acre. This led to an undeclared land war between the squatters and selectors.

Ned soon found that people had long memories for such as he. He ran in a wild bull and heard that James Whitty, a wealthy property owner on the King, had accused him of stealing it. He stopped him on Oxley racecourse and asked for an explanation. It must have been with some discomfiture that Whitty, a rugged character of Irish extraction like Ned himself, was forced to admit that his son in law, John Farrell, had fed him the rumour. The missing animal, in fact, had since turned up.

Max Brown Australian Son

The selectors blamed the squatters for the failure of selections as the best land had already been taken up. At the height of the battle some squatters would resort to harassment if all else failed. Selectors stock would be impounded, their fences broken down, their water flows restricted, and the squatters cattle would graze on the selectors lands. Whitty was one such squatter and along with McBean, was seen by the Kellys, Quinns, Byrnes and the like as men above the law who are able to direct the wrath of the police and magistrates on whom ever they pleased. That many of the selectors were just poor farmers with no land education what-so-ever was of no real importance, the squatter had build himself up as a tall poppy and it was only a matter of time before someone came along to cut him down.

Whitty and his fellow squatters presented Sergeant Steele with an engraved sword to commemorate Ned’s capture at Glenrowan – Whitty must have been one of the few people Steele didn’t try and shoot during the siege.

*John Batman was one of the founding fathers of Melbourne; captured bushranger Matthew Brady; and played an instrumental part in the organisation of the ‘Black Line’ campaign to capture Tasmanian Aborigines. Batman wrote in his disarmingly frank memoirs about a raid on an Aboriginal camp in which he ordered his men to fire on the blacks as they ran for their lives. A woman and a child were captured and, the next morning, two badly-injured men were discovered. They told Batman that ten men were dead or would die. Batman’s account then records how the two male prisoners found it impossible to walk because of their injuries, so he felt obliged to have them shot. Luckily Batman died of syphilis at age thirty-eight. Syphilis apparently causes execrating pain before death. Good one John!